Tag: surgery

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Chaszar

When 17-year-old Oldenburg gelding Madison Avenue (by Madison x Olympic Ferro), known as “G6” in the barn, developed recurring fevers and concerning bloodwork in September 2025, his owner, Jennifer Chaszar, knew something wasn’t right. His primary veterinarian, Dr. John Lockamy, had been monitoring him closely at home at Lady Jean Ranch in Jupiter, FL, but as his inflammation markers climbed and his fever returned, Dr. Lockamy recommended a deeper look.

“G6 had developed a fever that returned after initial treatment, he had a low white blood cell count, and his serum amyloid A (SAA) level was elevated at 3,000 in his bloodwork,” Chaszar recalled. “Dr. Lockamy referred us to Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC) because we didn’t want to overlook a more serious underlying issue.”

SAA is the major acute phase protein in horses and is produced during the acute phase response, which is a nonspecific systemic reaction to any type of tissue injury. While usually very low or close to zero, that number will rapidly and dramatically increase with a systemic infection.

A Critical Revisit

G6 was initially treated at PBEC in Wellington, FL, in 2023 when he had recurring colic symptoms. What was initially thought to be ulcers was diagnosed through gastroscopy as delayed gastric emptying by Dr. Jordan Lewis. A change in diet, with an emphasis on the portion size at each feeding, helped increase motility in his digestive tract and eliminate symptoms for a time, but those returned two years later.

G6 arrived at PBEC on September 21, 2025, where he was evaluated by internal medicine specialist Dr. Emilee Lacey and intern veterinarian Dr. Rachael Davis. G6 had been experiencing intermittent fevers, lethargy, and colic signs. An abdominal ultrasound soon revealed a left dorsal displacement of his large colon, which thankfully resolved with supportive care.

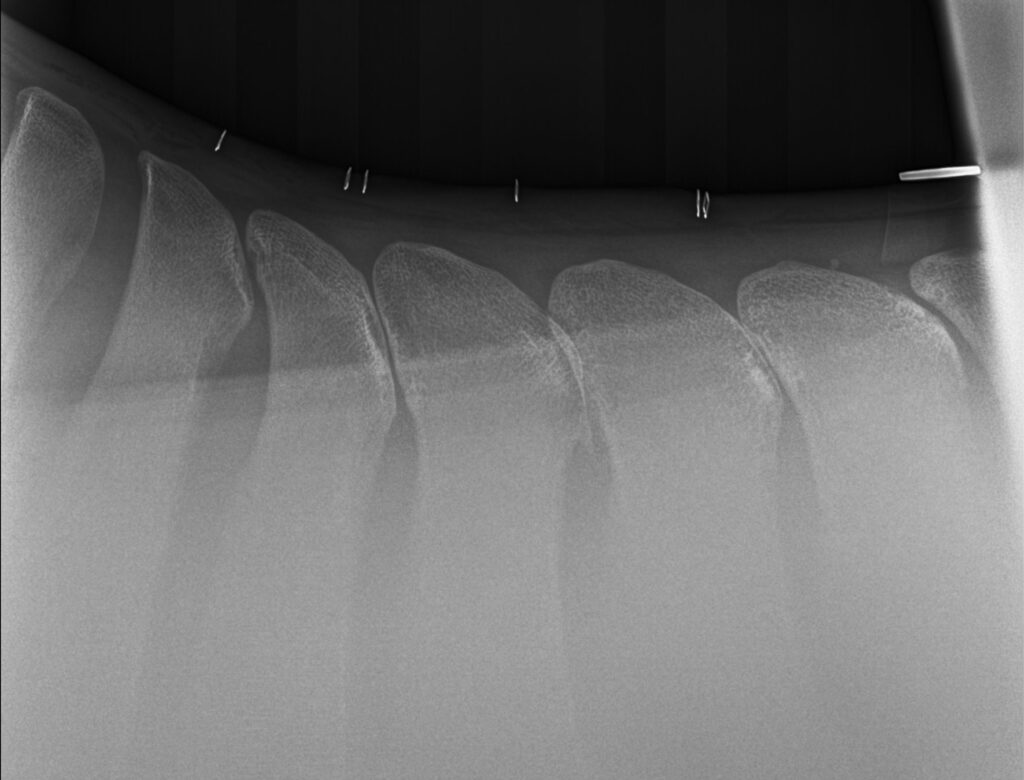

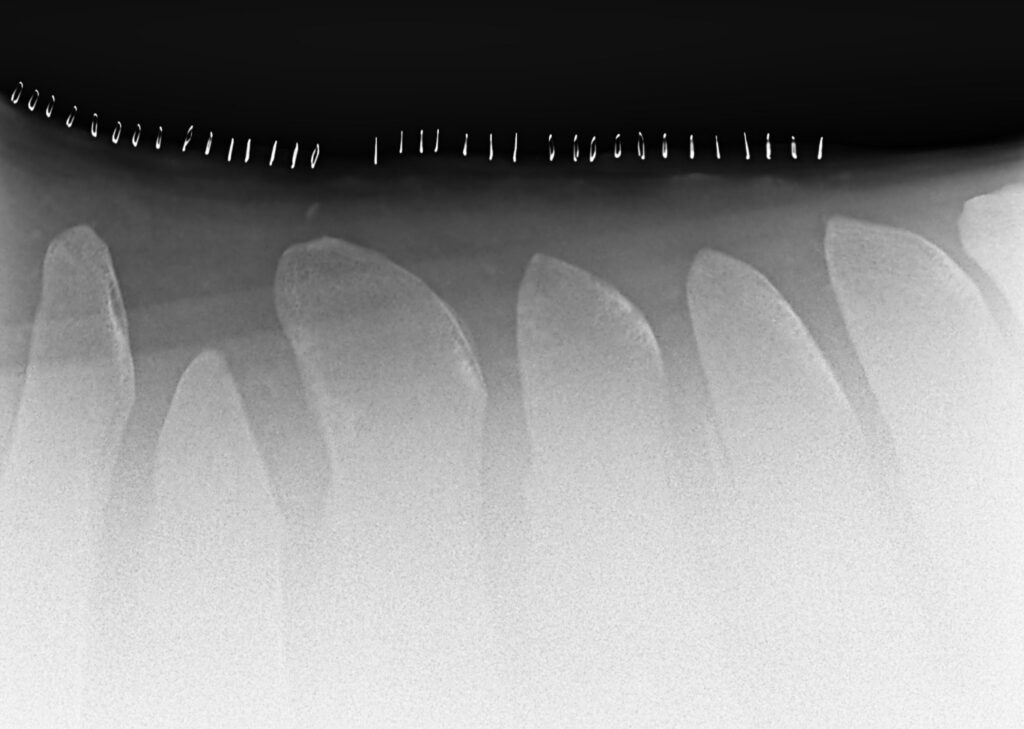

However, his bloodwork told a more complicated story. With inflammation still present, the PBEC team performed a gastroscopy to visualize the stomach lining. “The gastroscopy showed a few ulcerations of the squamous mucosa of the stomach and a nodular mass in the pyloric region,” said Dr. Davis. “The duodenum (first part of the small intestine) was mottled in appearance. Biopsy samples from both the pyloric mass and the duodenum were collected and submitted for histopathological analysis, which revealed evidence of inflammatory bowel disease.”

Chaszar remembered the relief she felt when the biopsy results returned. “The biopsies came back negative for malignancy,” she reported. “There was no evidence of cancer — just inflammatory changes. That provided tremendous relief and allowed us to focus on healing and recovery.”

G6 remained bright, cooperative, and comfortable during his stay, a testament to the attentive nursing and veterinary care he received.

Healing at Home

Dr. Lacey prescribed a thoughtful treatment plan that included gastroprotectants, dietary changes, and careful monitoring at home.

“Due to his known diagnosis of delayed gastric emptying and the suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we recommended trialing a diet that excluded wheat and his known allergies of corn, oats, rice bran, and carrots,” explained Dr. Lacey. “IBD has been loosely associated with gluten intolerance (wheat) in horses.”

Back home, Chaszar followed PBEC’s instructions closely to help support G6’s recovery. “His diet was modified to include softer, easily digestible forage and smaller, more frequent meals,” she noted. “I monitored his temperature, appetite, and demeanor every day to be sure he was progressing.”

Dr. Lacey and Dr. Davis also stressed the importance of daily exercise to promote normal gastrointestinal motility, hydration, and close communication with the veterinary team. They also wanted to see G6 back in 30 days for an examination.

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Chaszar

A Promising Recheck

Exactly one month later, G6 returned to PBEC for a scheduled recheck gastroscopy. Chaszar described this visit as a hopeful milestone. “His second visit was a one-day appointment designed to see how the pyloric nodule and inflammation had responded to treatment,” she said.

The news could not have been better. Dr. Lacey reported that the previously seen ulceration had completely resolved, and the pyloric nodule had reduced by about 75%, indicating that the treatment plan was working.

With that progress confirmed, G6 discontinued the gastroprotectants and continued with supportive nutrition and management. “It was wonderful to see that improvement,” said Chaszar. “His appetite has returned to normal, and his energy is strong. G6 is back to acting like a four-year-old! When I lead him to the arena, he nickers under his breath and then shows me the Spanish walk and downward dog tricks that he does before we move on to the serious part of work.”

A Testament to Exceptional Care

Chaszar credits PBEC’s team not only for their medical expertise but also for the warmth and professionalism that defined every interaction. “The entire PBEC team, from the front desk to the technicians, nurses, interns, and veterinarians, has been exceptional,” she shared. “They are proactive and collaborative in their approach, and their compassion, communication, and attention to detail are truly remarkable.”

She added that PBEC’s dedication sets the standard for equine veterinary medicine in South Florida. “Seeing G6 healthy, thriving, and back to himself reminds me of the incredible work PBEC does every day. I am especially grateful to Dr. Lacey and Dr. Davis for their thoroughness and dedication throughout his journey.”

Why Owners Trust Palm Beach Equine Clinic

For Chaszar, the most valuable part of the experience was PBEC’s collaborative, transparent approach. “Every veterinarian and staff member took the time to explain each step,” she said. “They even shared images from his scopes so I could fully understand his care. Their organization, genuine care, and follow-up are second to none. I am deeply thankful for their continued support.”

G6 is back to his regular routine, and his recovery journey highlights not only his resilience but also the power of skilled veterinary care and commitment to excellence.

Horse owners seeking a clinic that blends top-tier medicine with genuine empathy will find exactly that at Palm Beach Equine Clinic. G6’s story stands as one more shining example of the exceptional work they do every day. If you need first-class care for your horse or have questions, contact Palm Beach Equine Clinic at 561-793-1599. Visit www.EquineClinic.com for more information.

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Chaszar

Photo courtesy of NewStyle Digital.

Meet PBEC Veterinary Intern, Dr. Emma Newell, Palm Beach Equine Clinic’s New Internal Medicine Specialist

Dr. Newell earned her veterinary degree from the Royal Veterinary College in 2025 after completing her Animal Science (Pre-Vet) studies at Auburn University, where she graduated Summa Cum Laude in 2021. Growing up in the hunter/jumper community in Connecticut inspired her lifelong passion for equine health and her interest in sports medicine. She is dedicated to advancing her clinical skills and providing high-quality care to equine patients.

Outside of work, Dr. Newell enjoys staying active and returning to Connecticut whenever possible to spend time with her horse.

What has been your journey to becoming an equine veterinarian?

I grew up in the hunter/jumper industry, primarily showing ponies, and that’s where I discovered my passion for sports medicine. I attended an agricultural high school in Connecticut, where I was able to major in equine sciences. That experience drove me to study at Auburn University for my undergrad, majoring in animal science on the pre-veterinary track. I graduated Summa Cum Laude in 2021, and, from there, moved to London for school at the Royal Veterinary College. Being from Connecticut, and then moving down to Alabama, I got to see the differences in the horse industry throughout the country, and I wanted to take it to an international level.

What was it like adjusting to life in the United Kingdom, and what differences did you notice in veterinary medicine there versus the United States?

I had experienced London in earlier stages of my life, so the transition wasn’t hard for me. I loved the lifestyle and living over there. The horse care and equestrian community in the U.K. are both so strong that attending that school was a great decision for me.

I think some of our methods of treating sport horses are very different, like how we view the use of antimicrobials and medications. Having that perspective when treating sport horses here in the U.S. is important because it provides insight into the veterinary care they received overseas before being imported.

Photo courtesy of Emma Newell.

What interests you most about sports medicine?

I love performing lameness exams, and I love providing care to equine athletes. When I was showing, I was very driven, so bringing that mindset to veterinary medicine and seeing patients able to perform at the top level really motivates me.

What was the process for applying to become a PBEC intern?

The process includes completing an externship at PBEC, submitting your paperwork — which consists of your CV and letters of reference — and then participating in the interview phase.

What responsibilities does an intern have at PBEC?

As an intern, you do two-week rotations throughout the hospital. Rotations include anesthesia, surgery, ambulatory, and overnights, giving you experience working in all different environments, from surgical cases to in-depth internal medicine cases. During the anesthesia rotation, you are solely in charge of providing anesthesia to patients, whether that’s standing or general anesthesia for surgical patients – that’s quite interesting. For the surgery rotation, you are responsible for patient care in the hospital prior to and post-op, and you get subbed to scrub into surgeries. Ambulatory is my favorite rotation, and you’re on the road with vets who primarily provide ambulatory care, which is a great experience.

What’s it been like working with the team and the other interns at PBEC?

The team at Palm Beach Equine Clinic was something I was really excited about coming into this internship. We have a great, well-rounded group of veterinarians with diverse experiences and passions, which allows us to learn different things from each person. It’s the same with our intern team; we’re all well-rounded and have different strengths, and I think that that really pushes me as an individual to grow.

What advice would you give to students interested in equine veterinary medicine?

Take every chance to get hands-on experience. Put yourself out there and look for opportunities to learn under different equine veterinarians. Everyone has different life experiences and points of view, which is essential to making you into a well-rounded vet. As we all know, the horse world is quite small, so building connections throughout the community is definitely something that will help you.

The Last Leg of International Travel: CEM Quarantine

Whether returning home after a thrilling summer competing on the European circuits, traveling from a home base abroad, or importing a newly purchased equine, every horse entering the United States must follow specific guidelines based on the country of origin. Once the horse “clears customs” at the airport, satisfying United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) import requirements, there’s one more thing owners must consider before their horse reaches its final destination.

Mares and stallions remaining in the United States beyond the temporary stay period must undergo additional quarantine for Contagious Equine Metritis (CEM). This sexually transmitted bacterial infection can cause infertility in mares and is carried by stallions. While endemic in Europe, the disease is not currently in the U.S., so testing and quarantine for horses entering the country from areas with confirmed cases are essential to maintain that disease-free status.

Fortunately for horses traveling to Florida, Palm Beach Equine Clinic’s Dr. Jordan Lewis works closely with Richard Faver at Ossian Ventures, one of the largest commercial CEM quarantine facilities in Florida, to oversee and conduct the rigorous testing process, which differs based on whether the animal is a mare or stallion.

“Mares are usually with us for about 15 days. They need three sets of negative cultures, 72 hours apart, and then five days of washing with chlorhexidine and applying silver sulfadiazine as a topical treatment, which we call ‘clean and pack,’” explained Dr. Lewis, adding that they take samples from three areas of the mare and also pull a blood test, called a complement fixation (CF). The CF results and each set of cultures must be sent by mail to a lab for testing, and turnaround times are about a week for the cultures and a few days for the blood.

“Stallions are a little different,” continued Dr. Lewis, noting that their process takes about 35 days. Within the first few days, a culture is taken from the stallion and sent for testing.

“When the culture comes back negative, we have a set of mares called test mares that are cycled and ready to breed,” she said. “Those stallions live cover two test mares, which then start getting cultured on day three post-breeding. They go through the same process as the other mares: three sets of cultures, 72 hours apart. Twenty-one days after breeding, they do the CF test on those mares.”

Dr. Lewis noted that the test mares undergo a process called “short cycling” to ensure they will not become pregnant from these breedings. Each stallion also receives a clean and pack treatment after breeding and can then be released once all testing returns negative.

Throughout the horse’s stay at Ossian Ventures, Dr. Lewis and other Palm Beach Equine Clinic veterinarians are available to provide any additional care the animal might need after its long journey, including Coggins testing, if necessary, in preparation for the next step in the horse’s travel plans. Owners are welcome to visit and ride during this time, given that horses are kept from interacting, and any equipment that touches the animal stays at the facility and is only used on that horse.

“I just enjoy being part of the process,” shared Dr. Lewis about her role in maintaining the health and safety of the horses in quarantine. “Plus, we certainly get to see some world-class horses coming through, which is fun.”

There are many factors to consider when traveling internationally with horses, but the Palm Beach Equine Clinic is dedicated to providing quality care at every step, from touchdown at the airport to quarantine and beyond. This is the final article in a three-part series by Palm Beach Equine Clinic veterinarians detailing the rules and procedures of importing and exporting horses. Read part one on exporting horses by Dr. Janet Greenfield, followed by her second article on importing horses for temporary stays in the October and November issues of The Plaid Horse magazine. Contact Palm Beach Equine Clinic at 561-793-1599 for any equine health needs.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Emilee Lacey

Learn More About Dr. Emilee Lacey, Palm Beach Equine Clinic’s New Internal Medicine Specialist

Dr. Emilee Lacey grew up in California, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 2021, and completed an internship at Sports Medicine Associates of Chester County in Cochranville, PA. She has been immersed in the sport horse world her entire life, but her passion for managing fevers, respiratory disorders, and neurologic disease led her away from lameness exams and toward internal medicine. Dr. Lacey completed her large animal internal medicine residency and obtained a Master’s of Science in Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, VA, this summer. She joined Palm Beach Equine Clinic in August 2025.

What first sparked your love of horses?

My love for horses started at a very young age, but it was really nurtured by my horse-loving grandmother, aunt, and mom. After what felt like years of begging, my mom finally put me in horseback riding lessons when I was in grade school. After about a year of consistent riding, I convinced my mom to let us buy my aunt’s horse, Chili, an off-the-track Thoroughbred (OTTB) that was barely restarted and literally lived across the country in Maryland. She came off the trailer in California like a typical green OTTB: head straight up in the air, nostrils flared, and breathing like a dragon. I was only seven years old at the time, and I thought this was the BEST DAY EVER. My trainer had very different thoughts. This mare not only taught me to ride; she also taught me valuable horsemanship skills I still utilize today. Many other horses have come after Chili, but this mare will always be the spark that truly ignited my love for horses.

What inspired you to become a large animal veterinarian?

I’ve known I wanted to be a veterinarian since I was three years old. I halfheartedly joke that the words “I want to be a vet” were actually my first coherent words. I spent my childhood years obsessed with every TV show or movie that even slightly mentioned veterinary medicine, earned every Girl Scout patch remotely related to veterinary medicine or animals, and volunteered as much time as I could in any clinic or with any equine veterinarian that would take me.

When I finally made it to veterinary school, I was convinced I had to be a small animal veterinarian to have time for my own horses. I was so wrong! During my studies at the University of Pennsylvania, I met many vets who had their own horses and hobbies while maintaining an excellent work-life balance. I also realized that not only was I more interested in large animal medicine, but I was also better at it because I could connect with the owners. I am a horse owner first, and a veterinarian second. I understand how these special animals can become a part of your family.

After veterinary school, I completed an internship with Sports Medicine Associates of Chester County in Pennsylvania. I developed a special interest in managing poor performance that is not related to lameness. Diseases like Equine Asthma, myofibrillar myopathy, gastric ulceration, chronic hepatopathy, and heart murmurs all pulled me away from lameness exams and toward internal medicine. After my internship, I was humbled and honored to complete a large animal internal medicine residency at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in Blacksburg, VA. This three-year-long opportunity was a lot of hard work, but I loved every minute. When you love what you do, it doesn’t feel like work. I truly have the best job in the world!

Photo courtesy of Dr. Emilee Lacey.

How did that path lead you to Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

I found my way to Palm Beach Equine Clinic through a few mutual patients while completing my residency in Internal Medicine at Virginia Tech. While caring for these patients in the hospital, I was collaborating with [PBEC Founder] Dr. Paul Wollenman almost daily for a few weeks. During this time, [PBEC President] Dr. Scott Swerdlin reached out to me to gauge my interest in a job opportunity with PBEC. I was so impressed with the communication and collaboration among the veterinarians at this hospital, but what really convinced me was their dedication to excellent patient care. At PBEC, care doesn’t stop when an animal is discharged. The veterinarians here will continue to check in on your horse long after they’ve returned to the barn, and there’s also a team of other veterinarians, technicians, and support staff ready to help you if needed.

What are your current responsibilities or areas of focus at PBEC?

My current area of focus at PBEC is equine internal medicine. This is a specialized branch of veterinary medicine that focuses on the diagnosing and treating diseases affecting internal organ systems, including the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, liver, endocrine system, central nervous system, and others. I primarily care for patients in the hospital that require intensive care, but I also dedicate time to recheck examinations and consultations in the field. I tell my friends and family that my job is similar to a human physician working in an intensive care unit in a hospital.

What does a typical day on the job look like for you?

A typical day starts with morning rounds with our associate veterinarians, surgeons, and intern veterinarians to review the status of our current inpatients and update their treatment plans. After rounds, I review any completed daily bloodwork and complete any pending diagnostics, like recheck ultrasound examinations or a gastroscopy, for the current inpatients. I might spend the afternoon at nearby farms completing recheck examinations on previous patients, consulting on new cases from other veterinarians, or conducting an outpatient appointment in the hospital. I am also available for incoming emergency admissions, which can happen quite frequently and without much notice! At the end of every day, I round again with our intern veterinarians, which ensures excellent patient care in a collaborative environment.

What do you enjoy most about being part of the PBEC team?

My favorite part of working at PBEC is the ability to collaborate openly with veterinarians of different specialties and backgrounds. A person simply cannot know everything, and there is always more than one right way to do something. It’s really special to be able to walk down a hallway and talk to three different surgeons about their experiences with a certain diagnosis!

What new technology or recent advancements in veterinary medicine do you find most exciting?

I am most excited about recent advancements in therapeutic options for the management of equine metabolic disease (EMS). EMS is a common endocrine disorder associated with a horse’s inability to regulate their insulin levels – similar to “pre-diabetes” in humans. Horses with EMS are at high risk of developing laminitis, which can be life threatening. Historically, EMS was only managed with dietary changes and the limited efficacy of a short list of medications.

Now with the current use of ertugliflozin, a medication belonging to a class of drugs called sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, we have another option to reduce a horse’s insulin level in an attempt to prevent laminitis. Further studies are needed regarding long-term use, but we have seen some promising results over the last few years in clinical practice. As a horse owner who lost her heart horse to laminitis, it is really rewarding to help horses who suffer from this condition now.

What’s the most challenging part of being an equine veterinarian, and how do you handle it?

The most challenging part of being an equine veterinarian is convincing young, aspiring veterinarians to join our field! We are facing a national crisis due to the shortage of large animal veterinarians. More newly graduated veterinarians are entering small animal practice, there is an increased rate of early-career equine veterinarians leaving the profession, and a significant number of equine veterinarians are nearing retirement. One of my goals as an equine veterinarian is to show the younger generation that this is the best job in the world. I try to create a welcoming environment for learning by hosting externs and teaching interns every chance I can get. We need more horse vets!

What’s the most rewarding part about serving the equestrian community?

The most rewarding part of serving the equestrian community is having the opportunity to give back to the community that gave me so much growing up. I was so blessed to be surrounded by such thoughtful and caring horse trainers, owners, and veterinarians who cared for me like I was family. I was raised in the horse world, and it’s surreal and humbling to be able to care for these special animals during their most vulnerable times. I hope I never have to meet you and your horse in the hospital during an emergency, but if I do, I understand what it’s like to be the emotional owner! I’m here to care for your horse and support you in whatever decisions we need to make for them.

Is there a particular case or experience you’ve had at PBEC that has been especially meaningful to you?

My first few weeks at PBEC have been filled with some unusual cases, but one pony in particular has gained a special place in my heart. This pony was sick for a few days before being admitted to the hospital. Upon initial examination, I diagnosed an intra-abdominal mass. Through aggressive supportive care as well as anti-inflammatory and antibiotic medicines, this mass has decreased substantially in size, and the pony was able to go home. This pony went from being dull and not eating to being very difficult to catch and developing a voracious appetite. I recently received a video of him playing in a sprinkler at home. Success stories like this remind me of why I chose to pursue this career.

What advice would you share with those who dream of becoming equine veterinarians one day?

To those horse-crazy girls and boys thinking of being an equine veterinarian, don’t give up on your dream! Take every opportunity you can to be around horses, and network with any veterinarian you can. Be brave and introduce yourself – most of us love to chat about this job. If you find yourself in Florida, don’t hesitate to contact PBEC to set up an externship. We need you to join our profession!

Photo courtesy of Dr. Emilee Lacey.

When you’re not at work, what do you enjoy doing to relax and recharge?

When I’m not at work, you can catch me riding my horse, William, a 16-year-old OTTB gelding who has had me wrapped around his hoof since he was three years old. I have had this horse just a few months longer than I have known my husband, Mike. When I’m not at the barn, Mike and I enjoy walking our dogs on the beach, scuba diving, or simply enjoying a sunny afternoon at the pool with our family. It’s so important to have an identity outside of being a veterinarian, and I aim to be that example!

Where are you from?

I was born and raised in Switzerland, where we speak four national languages —German, French, Italian, and Romansh (an old Swiss tongue that’s still hanging on). I’m from Geneva, which is in the French-speaking part of the country and the best Swiss

city in my humble opinion.

Where did you earn your degree?

In Switzerland, you can only earn a veterinary degree in the German-speaking part. When I was just four years old, I asked my mom if it was possible to have a vocation because I already felt like mine was becoming a veterinarian. Thanks to my parents’

unwavering support, I was able to attend a bilingual school to learn German properly. I eventually studied veterinary medicine at the University of Zurich, which is in the largest city in Switzerland. Back home, veterinary school is structured into a three-year

Bachelor’s program followed by a two-year Master’s. After completing both, we take the federal veterinary licensing exam to become fully qualified.

What is your background with horses?

I started riding when I was three years old and later competed in show jumping for almost 10 years. I had to pause during vet school, but horses have always remained the love of my life. I used to say that my passion wasn’t actually show jumping — it was

taking care of my horses, spending time with them, and getting to know them like my own friends.

What brought you to PBEC?

I did a four-week externship at PBEC about two and a half years ago and was absolutely starstruck by the level of equine medicine practiced here. The variety of disciplines and cases, combined with the opportunity to learn new ways of practicing,

made me determined to come back.

I love sports medicine, and here you get to see everything — dressage, show jumping, polo, barrel racing, bucking horses, pleasure horses, and even Thoroughbreds. Each discipline brings its own veterinary challenges, and that variety is what makes PBEC so exciting. The clinic’s facilities and the range of specialties, from sports medicine and internal medicine to reproduction and ophthalmology, make it an incredible place to learn. Also, doing an internship in a private clinic rather than a university allows me to practice more hands-on medicine and grow more confident and independent in my clinical decision-making.

What was the process of becoming an intern?

Honestly, it was easier than I expected, thanks to the amazing support from Dr. Swerdlin and his team. I filled out a couple of forms, submitted some documents, made a quick visit to the U.S. Embassy in Switzerland, and I was good to go. They really made the whole process smooth and stress-free. Once I arrived, I had to schedule an appointment to get a Social Security number.

As an international intern, I was a bit worried about housing and transportation, but the clinic has everything well thought out. We’re provided with free housing in a lovely house surrounded by nature, and the company also offers cars for international interns who can’t purchase one at the time of arrival. PBEC really ensures we have great living conditions so that we can fully focus our energy on the internship.

What is the program like so far?

It’s definitely challenging — not just the workload but also being so far from my family and friends for the first time, adjusting to a new environment and the working world, as well as figuring out how to be the kind of veterinarian I want to become. It’s not always easy —internships aren’t for everyone — but I’m adapting.

My colleagues and supervisors have been incredibly supportive, and that makes a huge difference. This program exposes me to every corner of equine medicine, helping me decide what path I want to pursue in my career. And I get to learn from some of the

most experienced and generous equine vets out there.

when choosing an internship at PBEC. Photo courtesy of Sarah Océane Graf

What is a typical day like for you?

I usually get to the clinic around 6 and 7 a.m. to check on my patients and write their SOAPs (notes that stand for Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan). At 8:30 a.m., we have morning rounds with the surgical resident and clinicians where we go

over every patient, update their plans, and ask questions to better understand the cases.

After rounds, depending on my rotation, I might scrub into surgery, run anesthesia, or take in emergency cases. If I have a quieter moment, I’ll research my cases to deepen my understanding or help with outpatient procedures. I also just enjoy spending time

with the patients.

At 5:30 p.m., we do rounds with the overnight intern, who stays at the clinic until midnight (or later, depending on the case load) and is then on call until 8 a.m. One of the day interns is also on call for anesthesia each day.

What is something new that you’ve learned?

So much, and it’s only been a month. I can now confidently run general anesthesia, place arterial and venous catheters, perform abdominocentesis, and do a flash ultrasound. I even got to inject a coffin joint! I’ve also spent time in the reproduction

department and can now perform transrectal ultrasounds of the mare’s reproductive tract, do uterine flushes and infusions, and place urinary catheters. The list keeps growing, and I’m so grateful for the learning opportunities.

What do you do in your free time?

I brought my dog, Pepper, with me, so we spend time at the beach in Palm Beach or Jupiter, run around the neighborhood, or go to the dog park. In the evenings or on weekends, I read and re-read Harry Potter.

I’ve also discovered the wonders of Target, Whole Foods, and the mall… I may or may not have spent at least 24 hours there already.

And of course, I call my boyfriend… who patiently listens to me talk about transrectal ultrasounds while wondering where his life took a very specific turn.

Meet PBEC Intern Valentine Prié DVM

Valentine Prié DVM earned her veterinary degree in Croatia and spent time in several equine clinics in Europe before heading to the United States in 2024 to broaden her knowledge. She’s part of the class of 2024/2025 interns at the Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC) in Wellington, FL.

Where are you from?

I’m from Normandy in the northwest part of France. For the last six years, I have mostly lived in Croatia, where I did both my undergraduate and vet school work. In 2024, I moved to the U.S. and have been an intern at PBEC since July.

What is your background with horses?

I started riding when I was 5 years old. My family were ranchers, and we had a cattle and horse farm, so I was always around horses. I did mostly show jumping.

What brought you to PBEC?

I always wanted to be a vet — it was not even a question. My great-grandfather founded a vet school in France, and my brother is also going to graduate as an equine vet. It’s in the family!

I moved to Croatia shortly after turning 18 and graduated from the University of Zagreb’s vet school. During my fifth year, I spent some time in Austria at the University of Vienna. This year, I completed part of my final rotation at UC Davis in California.

I wanted to explore as many different approaches to equine medicine as possible. Things here in the U.S. are done differently, not just technique, but the approach to patient care and communication and the use of medications. My goal is to have, as much as possible, an open mind to veterinary practice.

When I complete the program at PBEC, I will head to going to Hagyard in Kentucky for a specialized internship.

What is the process of becoming an intern at PBEC?

I came to PBEC two years ago for a summer externship. After staying in touch with some previous interns and employees at the clinic, I applied last winter, had my interview in February, and in March, Dr. Swerdlin started helping me with the visa process. I began the internship in July.

What is the program like?

It’s been busy! I want to see as much as possible and experience all the areas of equine medicine — surgery, internal medicine, and ambulatory as well. It’s a really busy clinic with a high caseload and many veterinarians from various parts of the world, each withdifferent approaches to medicine and slightly different practices. That’s really beneficial for me to compare what can be done. It’s been a great learning experience. I see a lot and try to listen and remember!

What’s a typical day like for you?

Our schedule is organized on rotation, so we do two weeks of anesthesia, two weeks of surgery, two weeks of hospitalization/internal medicine, two weeks of ambulatory, and two weeks of overnight. Depending on which rotation I am on, the day is different.

Usually, you check the patients assigned to you for your rotation — I will do a full physical examination and write notes for every patient. After rounds, we get everything ready; for instance, with surgery, we bring the horse and assist with the surgery and the recovery of our patient. Then we take care of their treatment plan.

What do you do in your free time?

I’m a runner. I’m preparing for the Miami Marathon in February. I did the Toronto Marathon in 2024. And I read! I love all the French classical novels and poetry. I read a lot of equine medicine articles and books, too.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is one of the foremost equine surgical centers in the world with three board-certified surgeons on staff, led by Dr. Weston Davis. As a busy surgeon, Dr. Davis has seen many horses with the dreaded “kissing spines” diagnosis come across his table. Two of his most interesting success stories featured horses competing in the disciplines of barrel racing and dressage.

Flossy’s Story

The words “your horse needs surgery” are ones that no horse owner wants to hear, but to Sara and Kathi Milstead, it was music to their ears. In 2016, Sara – who was 17 years old at the time and based in Loxahatchee, Florida – had been working for more than a year to find a solution to her horse’s extreme behavioral issues and chronic back pain that could not be managed. Her horse Two Blondes On Fire, a then-eight-year-old Quarter Horse mare known as “Flossy” in the barn, came into Sara’s life as a competitive barrel racer. But shortly after purchasing Flossy, Sara knew that something wasn’t right.

“We tried to do everything we could,” said Sara. “She was extremely back sore, she wasn’t holding weight, and she would try to kick your head off. We tried Regu-Mate, hormone therapy, magna wave therapy, injections, and nothing helped her. We felt that surgery was the best option instead of trying to continue injections.”

At the time, Sara and her primary veterinarian, Dr. Jordan Lewis of Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC), brought Flossy to PBEC for thorough diagnostics. They determined Flossy had kissing spines.

Kissing Spines Explained

In technical terms, kissing spines are known as overriding or impinging dorsal spinous processes. The dorsal spinous process is a portion of bone extending dorsally from each vertebra. Ideally, the spinous processes are evenly spaced, allowing the horse to comfortably flex and extend its back through normal positions. With kissing spines, two or more vertebrae get too close, touch, or even overlap in places. This condition can lead to restrictions in mobility as well as severe pain, which ultimately can lead to back soreness and performance problems.

“The symptoms can be extremely broad,” acknowledged Dr. Davis. “[With] some of the horses, people will detect sensitivity when brushing over the topline. A lot of these horses get spasms in their regional musculature alongside the spinous processes.” A significant red flag is intermittent, severe bad behavior, such as kicking out, bucking, and an overall negative work attitude, something that exactly described Flossy.

Lakota’s Story

With dressage horse Lakota owned by Heidi Degele, there were minimal behavior issues, but Degele knew there had to be something more she could do to ease Lakota’s pain.

“As his age kicked in, it was like you were sitting on a two-by-four,” Heidi said of her horse’s condition. “I knew his back bothered him the most because with shockwave he felt like a different horse; he felt so supple and he had this swing in his trot, so I knew that’s what truly bothered him.” Though she could sense the stiffness and soreness as he worked, he was not one to rear, pin his ears, or refuse to work because of the pain he was feeling.

Heidi turned to Dr. Davis, who recommended a surgical route, an option he only suggests if medical treatment and physical therapy fail to improve the horse’s condition. “Not because the surgery is fraught with complications or [tends to be] unsuccessful,” he said, “but for a significant portion of these horses, if you’re really on top of the conservative measures, you may not have to opt for surgery.

“That being said, surgical interventions for kissing spines have very good success rates,” added Dr. Davis. In fact, studies have shown anywhere from 72 to 95 percent of horses return to full work after kissing spines surgery.

After Lakota made a successful recovery from his surgery in 2017, he has required no maintenance above what a typical high-level performance horse may need. Heidi attributes his success post-surgery to proper riding, including ground poles that allow him to correctly use his back, carrot stretches, and use of a massage blanket, which she has put into practice with all the horses at her farm. Dr. Davis notes that proper stretching and riding may also prolong positive effects of injections while helping horses stay more sound and supple for athletic activities.

Lakota, who went from Training Level all the way up through Grand Prix, is now used by top working students to earn medals in the Prix St. Georges, allowing them to show off their skills and earn the qualifications they need to advance their careers.

Flossy’s Turnaround

Flossy was found to have dorsal spinous process impingement at four sites in the lower thoracic vertebrae. Dr. Davis performed the surgery under general anesthesia and guided by radiographs, did a partial resection of the affected dorsal spinous processes (DSPs) to widen the spaces between adjacent DSPs and eliminate impingement.

Sara took her time bringing Flossy back to full work. Within days of the surgery, Sara saw changes in Flossy, but within six months, she was a new horse.

“Surgery was a big success,” said Sara. “Flossy went from a horse that we used to dread riding to the favorite in the barn. It broke my heart; she was just miserable. I didn’t know kissing spines existed before her diagnosis. It’s sad to think she went through that pain. She’s very much a princess, and all of her behavioral problems were because of pain. Now my three-year-old niece rides her around.”

Sara and Flossy have returned to barrel racing competition as well, now that Sara graduated from nursing school, and have placed in the money regularly including two top ten finishes out of more than 150 competitors.

“I can’t even count the number of people that I have recommended Palm Beach Equine Clinic to,” said Sara. “Everyone was really great and there was excellent communication with me through every step of her surgery and recovery.”

By finding a diagnosis for Flossy and a way to ease her pain, Sara was able to discover her diamond in the rough and go back to the competition arena with her partner for years to come.

What To Expect After the Unexpected Strikes

Featured on Horse Network

Every owner dreads having to decide whether or not to send their horse onto the surgical table for colic surgery. For a fully-informed decision, it is important that the horse’s owner or caretaker understands what to expect throughout the recovery process.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC) veterinarian Weston Davis, DVM, DACVS, assisted by Sidney Chanutin, DVM, has an impressive success rate when it comes to colic surgeries, and the PBEC team is diligent about counseling patients’ owners on how to care for their horse post-colic surgery.

“After we determine that the patient is a strong surgical candidate, the first portion of the surgery is exploratory so we can accurately define the severity of the case,” explained Dr. Davis. “That moment is when we decide if the conditions are positive enough for us to proceed with surgery. It’s always my goal to not make a horse suffer through undue hardship if they have a poor prognosis.”

Once Dr. Davis gives the green light for surgical repair, the surgery is performed, and recovery begins immediately.

“The time period for the patient waking up in the recovery room to them standing should ideally be about 30 minutes,” continued Dr. Davis. “At PBEC, we do our best to contribute to this swift return by using a consistent anesthesia technique. Our team controls the anesthesia as lightly as we can and constantly monitors blood pressure. We administer antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-endotoxic drugs, and plasma to help combat the toxins that the horse releases during colic. Our intention in the operating room is to make sure colic surgeries are completed successfully, but also in the most time-efficient manner.”

Colic surgery recovery often depends on the type and severity of the colic. At the most basic level, colic cases can be divided into two types – large intestine colic and small intestine colic – that influence the recovery procedures and outlook.

Large intestinal colic or impaction colic is characterized by the intestine folding upon itself with several changes of direction (flexures) and diameter changes. These flexures and diameter shifts can be sites for impactions, where a firm mass of feed or foreign material blocks the intestine. Impactions can be caused by coarse feeds, dehydration, or an accumulation of foreign materials such as sand.

Small intestinal colic or displacement colic can result from gas or fluid distension that results in the intestines being buoyant and subject to movement within the gut, an obstruction of the small intestine, or twisting of the gut. In general, small intestinal colics can be more difficult than large intestinal colics when it comes to recovery from surgery.

“Many people do assume that after the colic surgery is successfully completed their horse is in the clear,” said Dr. Chanutin. “However, during the first 24 to 48 hours after colic surgery, there are many factors that have to be closely monitored.

“We battle many serious endotoxic effects,” continued Dr. Chanutin. “When the colon isn’t functioning properly, microbial toxins are released inside the body. These microbials that would normally stay in the gastrointestinal tract then cause tissue damage to other bodily systems. We also need to be cognizant of the possibility of the patient developing laminitis, a disseminated intervascular coagulation (overactive clotting of the blood), or reflux, where a blockage causes fluids to back up into the stomach.”

Stages after surgery

Immediately Post-Surgery

While 30 minutes from recumbent to standing is the best-case scenario, Dr. Davis acknowledges that once that time period passes, the surgical team must intervene by encouraging the horse to get back on its feet.

Once a horse returns to its stall in the Equine Hospital at PBEC, careful monitoring begins, including physical health evaluations, bloodwork, and often, advanced imaging. According to Dr. Davis, physical exams will be conducted at least four times per day to evaluate the incision and check for any signs of fever, laminitis, lethargy, and to ensure good hydration status. An abdominal ultrasound may be done several times per day to check the health of the gut, and a tube may be passed into the stomach to check for reflux and accumulating fluid in the stomach.

“The horse must regularly be passing manure before they can be discharged,” said Dr. Chanutin. “We work toward the horse returning to a semi-normal diet before leaving PBEC. Once they are at that point, we can be fairly confident that they will not need additional monitoring or immediate attention from us.”

Returning Home

Drs. Davis and Chanutin often recommend the use of an elastic belly band to support the horse’s incision site during transport from the clinic and while recovering at home. Different types of belly bands offer varying levels of support. Some simply provide skin protection, while others are able to support the healing of the abdominal wall.

Two Weeks Post-Surgery

At the 12-to-14-day benchmark, the sutures will be removed from the horse’s incision site. The incision site is continuously checked for signs of swelling, small hernias, and infection.

At-Home Recovery

Once the horse is home, the priority is to continue monitoring the incision and return them to a normal diet if that has not already been accomplished.

The first two weeks of recovery after the horse has returned home is spent on stall rest with free-choice water and hand grazing. After this period, the horse can spend a month being turned out in a small paddock or kept in a turn-out stall. They can eventually return to full turnout during the third month. Hand-walking and grazing is permittable during all stages of the at-home recovery process. After the horse has been home for three months, the horse is likely to be approved for riding.

Generally, when a horse reaches the six-month mark in their recovery, the risk of adverse internal complications is very low, and the horse can return to full training under saddle.

When to Call the Vet?

Decreased water intake, abnormal manure output, fever, pain, or discomfort are all signals in a horse recovering from colic surgery when a veterinarian should be consulted immediately.

Long-Term Care

Dr. Davis notes that in a large number of colic surgery cases, patients that properly progress in the first two weeks after surgery will go on to make a full recovery and successfully return to their previous level of training and competition.

Depending on the specifics of the colic, however, some considerations need to be made for long-term care. For example, if the horse had sand colic, the owner would be counseled to avoid sand and offer the horse a selenium supplement to prevent a possible relapse. In large intestinal colic cases, dietary restrictions may be recommended as a prophylactic measure. Also, horses that crib can be predisposed to epiploic foramen entrapment, which is when the bowel becomes stuck in a defect in the abdomen. This could result in another colic incident, so cribbing prevention is key.

Generally, a horse that has fully recovered from colic surgery is no less healthy than it was before the colic episode. While no one wants their horse to go through colic surgery, owners can rest easy knowing that.

“A lot of people still have a negative association with colic surgery, in particular the horse’s ability to return to its intended use after surgery,” said Dr. Davis. “It’s a common old-school mentality that after a horse undergoes colic surgery, they are never going to be useful again. For us, that situation is very much the exception rather than the rule. Most, if not all, recovered colic surgery patients we treat are fortunate to return to jumping, racing, or their intended discipline.”

When the Bone Breaks

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is Changing the Prognosis for Condylar Fracture Injuries

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is changing the prognosis for condylar fracture injuries in race and sport horses. Advances in diagnostic imaging, surgical skillset, and the facilities necessary to quickly diagnose, treat, repair, and rehabilitate horses with condylar fractures have improved dramatically in recent years.

Photo by Jump Media

Most commonly seen in Thoroughbred racehorses and polo ponies, a condylar fracture was once considered a career-ending injury. Today, however, many horses fully recover and return to competing in their respective disciplines.

What is a Condylar Fracture?

A condylar fracture is a repetitive concussive injury that results in a fracture to the cannon bone above the fetlock due to large loads transmitted over the cannon bone during high-speed exercise. On a radiograph, a condylar fracture appears as a crack that goes laterally up the cannon from the fetlock joint and out the side of the bone, essentially breaking off a corner of the cannon bone, sometimes up to six inches long.

“A condylar fracture is a disease of speed,” said Dr. Robert Brusie, a surgeon at Palm Beach Equine Clinic who estimates that he repairs between 30 and 50 condylar fractures per year. “A fracture to the left lateral forelimb is most common in racehorses as they turn around the track on a weakened bone and increased loading.”

Condylar fractures are further categorized into incomplete and non-displaced (the bone fragment hasn’t broken away from the cannon bone and is still in its original position), or complete and displaced (the fragment has moved away from the cannon bone itself and can often be visible under the skin).

Additionally, condylar fractures can occur laterally or medially. According to fellow Palm Beach Equine Clinic surgeon Dr. Weston Davis, most condylar fractures tend to be lateral on the outside condyle (a rounded projection on a bone, usually for articulation with another bone similar to a knuckle or joint).

“Most lateral condylar fractures are successfully repaired,” said Dr. Davis. “Medial condylar fractures tend to be more complicated configurations because they often spiral up the leg. Those require more advanced imaging and more advanced techniques to fix.”

What is the Treatment?

The first step in effectively treating a condylar fracture through surgery is to accurately and quickly identify the problem. Board-certified radiologist Dr. Sarah Puchalski utilizes the advanced imaging services at Palm Beach Equine Clinic to accomplish exactly this.

“Stress remodeling can be detected early and easily on nuclear scintigraphy before the horse goes lame or develops a fracture,” said Dr. Puchalski. “Early diagnosis of stress remodeling allows the horse to be removed from active race training and then return to full function earlier. Early diagnosis of an actual fracture allows for repair while the fracture is small and hopefully non-displaced.”

Photo by Jump Media

Once the injury is identified as a condylar fracture, Palm Beach Equine Clinic surgeons step in to repair the fracture and start the horse on the road to recovery. Depending on surgeon preference, condylar fracture repairs can be performed with the horse under general anesthesia, or while standing under local anesthesia. During either process, surgical leg screws are used to reconnect the fractured condyle with the cannon bone.

“For a small non-displaced fracture, we would just put in one to two screws across the fracture,” explains Dr. Davis. “The technical term is to do it in ‘lag fashion,’ such that we tighten the screws down heavily and really compress the fracture line. A lot of times the fracture line is no longer visible in x-rays after it is surgically compressed. When you get that degree of compression, the fractures heal very quickly and nicely.”

More complicated fractures, or fractures that are fully displaced, may require additional screws to align the parts of the bone. For the most severe cases of condylar fractures, a locking compression plate with screws is used to stabilize and repair the bone.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic surgeon Dr. Jorge Gomez approaches a non-displaced condylar fracture while the horse is standing, which does not require general anesthesia.

“I will just sedate the horse and block above the site of the fracture,” said Dr. Gomez. “Amazingly, horses tolerate it really well. Our goal is always to have the best result for the horse, trainers, and us as veterinarians.”

According to Dr. Gomez, the recovery time required after a standing condylar fracture repair is only 90 days. This is made even easier thanks to a state-of-the-art standing surgical suite at Palm Beach Equine Clinic. The four-and-a-half-foot recessed area allows doctors to perform surgeries anywhere ventral of the carpus on front legs and hocks on hind legs from a standing position. Horses can forgo general anesthesia for a mild sedative and local nerve blocks, greatly improving surgical recovery.

“A condylar fracture was once considered the death of racehorses, and as time and science progressed, it was considered career-ending,” concluded Dr. Brusie. “Currently, veterinary medical sciences are so advanced that we have had great success with condylar fracture patients returning to full work. Luckily, with today’s advanced rehabilitation services, time, and help from mother nature, many horses can come back from an injury like this.”

Palm Beach Equine Clinic’s surgical team leader, Dr. Robert Brusie, is a nationally renowned board-certified surgeon whose surgical specialties include orthopedic, arthroscopic, and emergency cases. Dr. Brusie has been the head surgeon with Palm Beach Equine Clinic for the last 20 years and is a beloved part of the team.

Dr. Brusie graduated from Michigan State University (MSU) College of Veterinary Medicine. He completed his surgical residency at the Marion DuPont Scott Equine Center in Virginia in 1989 and has been in private practice ever since. He became a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons in 1994. Dr. Brusie joined the Palm Beach Equine Clinic team in 1996.

Board-certified surgeon, Dr. Brusie is recognized for his expertise in colic surgery, as well as for his skill in arthroscopic surgery. His surgical experience expands the clinic’s progressive care in both emergency and elective procedures. He has published articles on numerous topics, including the equine intestinal tract and septic arthritis in horses. Dr. Brusie is married and has three daughters. Read on to find out more about Dr. Brusie!

What is your background with horses?

I grew up on a farm in Michigan. We had usually between 200 and 600 head of cattle and always between four to six horses. Our horses were cow ponies or driving horses. My dad loved horses and had to have them around. My family has owned our farm for six generations and it pretty much occupied all of our time besides sports and school. Needless to say, we didn’t have much time to show horses.

When and why did you decide to become a veterinarian? Did you know you wanted to be a surgeon from the start?

I decided to become a veterinarian at an early age. I think I was seven or eight years old when I pulled my first calf. One of my dad’s hired men called me “Doc” when I was about that age. When I went to college, my plan was to become a large animal veterinarian and live in my hometown and continue to farm part-time with my three brothers. All of that changed when I was in veterinary school at MSU. Dr. Ed Scott was one of the five surgeons there; he was a gifted surgeon and a great teacher. He steered me into an equine internship at Auburn University. It was one of those things that the more you did, the more you wanted to do to improve yourself. I operated on my first colic by myself when I was three weeks out of vet school (32 years ago).

How did you first start working at Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

I was a surgeon at a clinic in Atlanta, and in 1996 I had performed a surgery for a client of Dr. Paul Wollenman’s. He had started this practice in 1975 and asked me if I needed a job. I was planning on staying in Atlanta for the rest of my career. I received phone calls from the other two partners over the next nine months, and eventually with encouragement from my fiancé, now wife, Melissa, I took the job.

What do you love most about working at Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

We have an exceptional group of veterinarians and staff here. The depth and scope of our veterinarians is amazing due to the large caseload. On any individual case, there may be two to three doctors that have input on the case to ensure no stone is left unturned. Additionally, we are so privileged to work on some of the best show, race, and polo horses in the world. It is truly an honor.

What sets the surgical services at Palm Beach Equine Clinic apart?

Between Dr. Jorge Gomez, Dr. Weston Davis, and myself, we perform just about every type of soft tissue and orthopedic surgeries that are done in our field. Personally, my greatest sense of success is when I see a horse back after surgery going as well or better than it was prior to surgery.

What are the biggest changes you have seen in sport horse medicine over the years?

Currently, the most exciting thing we see going on in medicine is regenerative therapy. Twelve to 15 years ago, we were harvesting bone marrow from the sternum and injecting it into lesions in tendons and ligaments. Now we manipulate the bone marrow or other sources of stem cells to promote more rapid and more functional healing of some of these injuries. I can assure you that in 10 to 20 years what we are doing now will seem stone-aged by then. There are some very clever minds performing some serious research in this field.

How do you stay up-to-date on new medical advances?

Every veterinarian at Palm Beach Equine Clinic tries to attend as many meetings as time allows. We also do a weekly journal club at our clinic to discuss recently published papers in veterinary and human medicine and surgery.

What is the most interesting or challenging surgery that you have done?

Dr. Gomez and I had a three-year-old racehorse that had split his P1 (long pastern bone) and cannon bone in the same leg in a race. We were able to piece together both bones perfectly and the horse recovered brilliantly. He probably could have returned to racing, however, the owners elected to retire him to life as a breeding stallion.

What is something interesting that people may not know about you?

I have three daughters who I am very proud of and tend to brag on maybe a little too much.

How else is the family involved in horses?

My wife [Melissa] and youngest daughter [Kayla] are horse nuts in the true sense of the word. Anything to do with horses, especially show hunters, they are dialed in. Melissa loves riding, and Kayla shows in hunters and equitation.

What makes Palm Beach Equine Clinic a special place for you?

I am blessed to have three good men as business partners. They are my good friends and great people. We are very lucky to have 20-plus veterinarians working with us who are very knowledgeable and caring individuals. We feel like a little practice, but with a lot of people who just get the job done.