What does a typical day look like for you at Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

My work is mainly sports medicine oriented. I do a lot of performance evaluations to make sure riders get the most out of their equine athletes every time they enter the ring. Also, pre-purchase exams are a large part of what I do, but every day is different. You never know what is going to come up on a daily basis. It’s what makes the job so great. There’s always something to learn from both the horses and their riders.

What aspects of equine medicine interest you most, and what types of cases do you find most rewarding?

What I really love is diagnosing and treating performance

problems. Sometimes very subtle problems can lead to more rails and lower results. The process of putting together all the pieces of the puzzle by really listening to the rider, taking a careful history, examining the horse, and then treating the horse, is so rewarding. Knowing you are part of the team that makes the horse and rider successful is very special.

Currently, I’ve been spending a lot of time diagnosing and treating neck and poll issues. The more we look in these areas, the more we are finding performance-related issues such as head tossing, head tilt, one-sided rein resistance, rooting, and lots of other symptoms we haven’t necessarily thought about in the past as being related to poll and neck discomfort.

Dr. Bryan Dubynsky

Photo courtesy of Jump Media

What do you enjoy most about working with performance horses?

The most enjoyable part would be when you see horses that you have treated and made better do well in competition. There’s nothing more satisfying than being part of the team and having a rider say, “He’s/she’s never felt so good!”

What has been one of your favorite moments while working for Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

There have been so many great moments at PBEC. It is so special when the entire team, from ambulatory vets, to surgeons, and everyone in between pulls together and turns challenging cases into successful outcomes. One particular case was when a horse had a full thickness abdominal laceration from a jump cup and his intestines were falling out. The attending horse show vet did perfect emergency first aid, the horse came to the clinic, and the whole team medicated and prepped for surgery. The surgeon patched him all up and the horse was competing again a few weeks later. That case really illustrated what a whole team effort looks like in achieving great outcomes.

When and why did you decide that you wanted to become a veterinarian?

My father is a physician, and I always had an interest in medicine. Choosing to become a veterinarian seemed to be a natural fit combining my love for horses and medicine.

Dr. Dubynsky performing a hind flexion test.

Photo courtesy of PBEC

What is some advice that you would give someone who wants to become a veterinarian?

Pick out the top people in the industry and work with them. Learn as much as you possibly can from the people who have been practicing for a long time.

What is something interesting that people may not know about you?|

I love to do woodworking projects like building tables.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is one of the foremost equine surgical centers in the world with three board-certified surgeons on staff, led by Dr. Weston Davis. As a busy surgeon, Dr. Davis has seen many horses with the dreaded “kissing spines” diagnosis come across his table. Two of his most interesting success stories featured horses competing in the disciplines of barrel racing and dressage.

Flossy’s Story

The words “your horse needs surgery” are ones that no horse owner wants to hear, but to Sara and Kathi Milstead, it was music to their ears. In 2016, Sara – who was 17 years old at the time and based in Loxahatchee, Florida – had been working for more than a year to find a solution to her horse’s extreme behavioral issues and chronic back pain that could not be managed. Her horse Two Blondes On Fire, a then-eight-year-old Quarter Horse mare known as “Flossy” in the barn, came into Sara’s life as a competitive barrel racer. But shortly after purchasing Flossy, Sara knew that something wasn’t right.

“We tried to do everything we could,” said Sara. “She was extremely back sore, she wasn’t holding weight, and she would try to kick your head off. We tried Regu-Mate, hormone therapy, magna wave therapy, injections, and nothing helped her. We felt that surgery was the best option instead of trying to continue injections.”

At the time, Sara and her primary veterinarian, Dr. Jordan Lewis of Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC), brought Flossy to PBEC for thorough diagnostics. They determined Flossy had kissing spines.

Kissing Spines Explained

In technical terms, kissing spines are known as overriding or impinging dorsal spinous processes. The dorsal spinous process is a portion of bone extending dorsally from each vertebra. Ideally, the spinous processes are evenly spaced, allowing the horse to comfortably flex and extend its back through normal positions. With kissing spines, two or more vertebrae get too close, touch, or even overlap in places. This condition can lead to restrictions in mobility as well as severe pain, which ultimately can lead to back soreness and performance problems.

“The symptoms can be extremely broad,” acknowledged Dr. Davis. “[With] some of the horses, people will detect sensitivity when brushing over the topline. A lot of these horses get spasms in their regional musculature alongside the spinous processes.” A significant red flag is intermittent, severe bad behavior, such as kicking out, bucking, and an overall negative work attitude, something that exactly described Flossy.

Lakota’s Story

With dressage horse Lakota owned by Heidi Degele, there were minimal behavior issues, but Degele knew there had to be something more she could do to ease Lakota’s pain.

“As his age kicked in, it was like you were sitting on a two-by-four,” Heidi said of her horse’s condition. “I knew his back bothered him the most because with shockwave he felt like a different horse; he felt so supple and he had this swing in his trot, so I knew that’s what truly bothered him.” Though she could sense the stiffness and soreness as he worked, he was not one to rear, pin his ears, or refuse to work because of the pain he was feeling.

Heidi turned to Dr. Davis, who recommended a surgical route, an option he only suggests if medical treatment and physical therapy fail to improve the horse’s condition. “Not because the surgery is fraught with complications or [tends to be] unsuccessful,” he said, “but for a significant portion of these horses, if you’re really on top of the conservative measures, you may not have to opt for surgery.

“That being said, surgical interventions for kissing spines have very good success rates,” added Dr. Davis. In fact, studies have shown anywhere from 72 to 95 percent of horses return to full work after kissing spines surgery.

After Lakota made a successful recovery from his surgery in 2017, he has required no maintenance above what a typical high-level performance horse may need. Heidi attributes his success post-surgery to proper riding, including ground poles that allow him to correctly use his back, carrot stretches, and use of a massage blanket, which she has put into practice with all the horses at her farm. Dr. Davis notes that proper stretching and riding may also prolong positive effects of injections while helping horses stay more sound and supple for athletic activities.

Lakota, who went from Training Level all the way up through Grand Prix, is now used by top working students to earn medals in the Prix St. Georges, allowing them to show off their skills and earn the qualifications they need to advance their careers.

Flossy’s Turnaround

Flossy was found to have dorsal spinous process impingement at four sites in the lower thoracic vertebrae. Dr. Davis performed the surgery under general anesthesia and guided by radiographs, did a partial resection of the affected dorsal spinous processes (DSPs) to widen the spaces between adjacent DSPs and eliminate impingement.

Sara took her time bringing Flossy back to full work. Within days of the surgery, Sara saw changes in Flossy, but within six months, she was a new horse.

“Surgery was a big success,” said Sara. “Flossy went from a horse that we used to dread riding to the favorite in the barn. It broke my heart; she was just miserable. I didn’t know kissing spines existed before her diagnosis. It’s sad to think she went through that pain. She’s very much a princess, and all of her behavioral problems were because of pain. Now my three-year-old niece rides her around.”

Sara and Flossy have returned to barrel racing competition as well, now that Sara graduated from nursing school, and have placed in the money regularly including two top ten finishes out of more than 150 competitors.

“I can’t even count the number of people that I have recommended Palm Beach Equine Clinic to,” said Sara. “Everyone was really great and there was excellent communication with me through every step of her surgery and recovery.”

By finding a diagnosis for Flossy and a way to ease her pain, Sara was able to discover her diamond in the rough and go back to the competition arena with her partner for years to come.

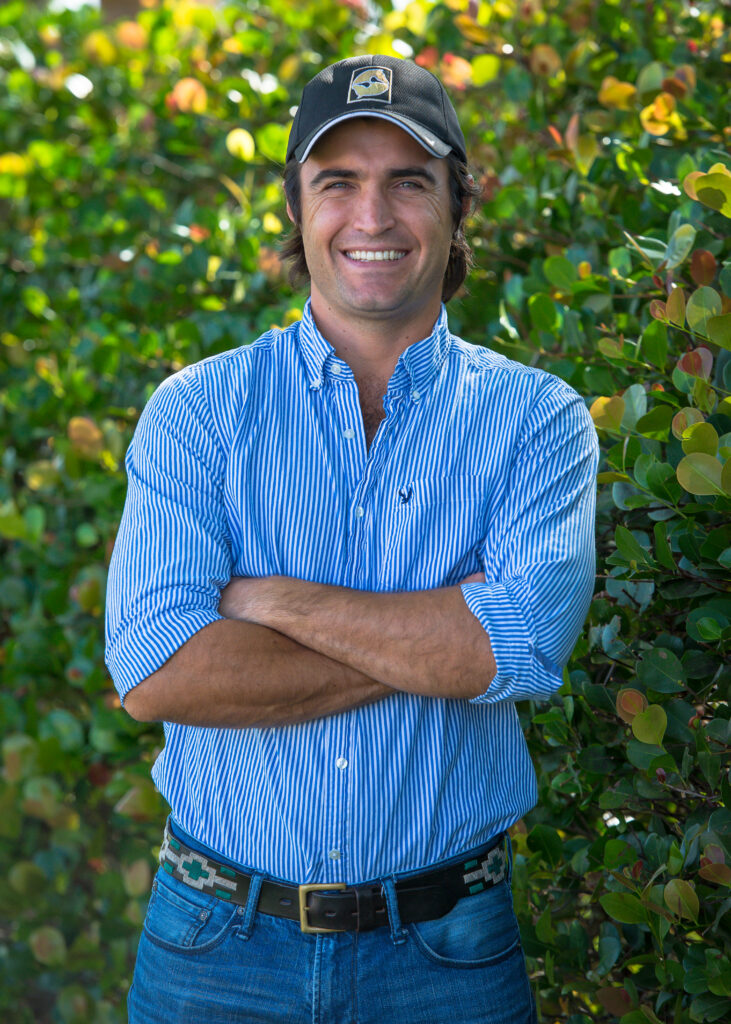

Dr. Santiago Demierre mainly focuses on equine performance medicine and specializes in the prevention and treatment of lameness in sport horses. Originally from Argentina, Dr. Demierre completed a certification program called the Educational Commission for Foreign Veterinary Graduates (ECFVG) through the American Veterinary Medicine Association to validate his degree in the United States. Dr. Demierre completed an internship at PBEC and went on to become a staff veterinarian.

What is your background with horses?

When I was little my father used to have racehorses and train them. I would spend hours with him and the horses at the farm. Later on, I had friends who worked with cows, and I also played a little polo.

Where are you originally from, and where did you complete your undergraduate degree?

I am from San Antonio de Areco, which is a small town in Argentina. I went to vet school at Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Dr. Santiago Demierre

Photo courtesy of PBEC

What inspired you to become an equine veterinarian?

I am not sure what exactly inspired me. I was always very interested in animals in general, not only horses. I have had the idea of becoming a veterinarian since I was five or six years old. I wanted to be able to spend as much time with animals as I could. I never thought of any alternative careers.

What advice would you give someone who wants to become an equine veterinarian?

I would tell them it is a great career, but to be aware that there is a lot of work and continuous studying ahead.

What does a typical day look like for you at PBEC?

I drive from barn to barn all day and look at lameness and performance horse cases mostly.

Dr. Santiago Demierre taking an x-ray.

Photo by Erin Gilmore Photography

What do you enjoy most about working at PBEC?

The team at PBEC is made up of great veterinarians and great friends. There is always somebody from whom you can learn something new every day. Also, it is awesome to be in contact with the world’s top equine athletes. That is what I enjoy most about being part of the team at PBEC—working on performance horse cases. More specifically, I really like preventing and treating lameness in sport horses.

When not at PBEC, what do you enjoy doing or where can we find you?

I love outdoor activities like fishing, hunting, and running as a workout. I also love cooking and red wine.

Featured on Horse Network

In order for a racehorse to successfully speed down the track, a jumper to navigate a quick and clear round, or a dressage horse to perform a picture-perfect test, the horse must have a healthy respiratory system.

Regardless of discipline or level of training, it is key to ensure a horse is breathing properly for its overall wellbeing.

If a horse is having respiratory problems, there are several ways that a veterinarian can investigate the issue. One of the most effective tools is a dynamic endoscope, a video recording device that can be worn by the horse during exercise to observe the respiratory system while they are active.

Respiratory Specialist, Dr. David Priest of Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC), focuses on upper airway diagnosis and surgery for equine athletes and often uses a dynamic endoscope to evaluate his patients.

The equine respiratory system is responsible for bringing large amounts of oxygen in and out of the lungs, where it is then used to fuel complex bodily processes. It comprises two sections, the upper and lower airways. The upper airway begins with the nostrils and extends through the larynx and into the trachea. The lower airway is made up of the lungs, which rest behind the shoulder, extend up the back, and reach toward the end of the ribcage.

Dr. David Priest

Photo by Jump Media

“Even a small decrease in lung capacity or impingement on airflow can have dramatic effects on overall health and performance,” described Dr. Priest. “Problems affecting the upper and lower airways may overlap but can include coughing or odd noises, exercise intolerance, nasal discharge, or labored breathing at rest.”

During exercise, the amount of air moved in and out of the horse increases proportionately to how hard the horse is working. The more demanding the work, the more oxygen must be used. A horse at rest inhales approximately 3.5 liters of air per second (L/s), and increases exponentially to 70 L/s at maximum exertion, according to Dr. Priest.

“If a horse is showing signs of difficulties in its respiratory health, veterinarians may use radiography or ultrasound to image the lungs,” explained Dr. Priest. “Going beyond greyscale images [such as radiographs], the veterinarian may also evaluate the upper respiratory tract through the use of an endoscope. An endoscope is a medical device with a small lens on the end that can be inserted through the horse’s nostril to view the horse’s pharynx.”

A dynamic endoscope on a harness race horse.

Photo courtesy of PBEC

If a horse is having trouble breathing only while working, it is necessary for a veterinarian to be able to evaluate them while they are active. To perform that assessment, a dynamic endoscope is used. This allows veterinarians to examine the horse’s pharynx, epiglottis, and trachea in motion. The dynamic endoscope will detect throat abnormalities and provide more information on respiratory issues or problems that are not seen when the horse is resting.

“The soft tissue structures of the horse’s upper airway experience a significant amount of force when the horse is exercising,” remarked Dr. Priest. “There is also a significant difference in resting and exercising forces, and this causes the upper airway tissues to appear anatomically normal at rest, even if they are functioning abnormally during exercise.”

A dynamic endoscope is often used with horses that have recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, commonly known as “roaring.” Recurrent laryngeal neuropathy restricts the amount of air able to reach the lungs through the horse’s upper respiratory system. This is a useful tool to diagnose the problem and also to evaluate the effectiveness of the surgery.

Respiratory difficulties during exercise can have a significant negative impact on a horse’s health and performance. A dynamic endoscope is a valuable and informative tool in Equine Sports Medicine. Once the issue is identified, there are several treatment or surgical options to address specific respiratory illness. If your horse is making an abnormal noise during exercise, or if you suspect breathing problems, contact your veterinarian to make sure your horse is performing at its best.

Where are you originally from, and where did you complete your undergraduate degree?

I am originally from Prince Edward Island, Canada. I completed my undergraduate degree and veterinary school there. I then did my surgery residency at Auburn University in Auburn, AL.

What does a typical day look like for you at Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

Most of my time at Palm Beach Equine Clinic is spent splitting the surgery on-call with Dr. Weston Davis and Dr. Robert Brusie. When I am there, you are most likely to see me doing colic surgery. Outside of those responsibilities, I work for Shane Sweetnam at Sweet Oak Farm as a staff veterinarian. I oversee all aspects of those horses’ routines and preventative care spending time at their farm and at the Winter Equestrian Festival (WEF). I also enjoy the challenge of performance evaluations.

Photo courtesy of Liz Barrett

What aspects of equine medicine interest you most, and what types of cases do you find most rewarding?

I really enjoy performance horse issues. The cases that interest me the most are those dealing with horses that are competing at the top level of their sport. I like helping maintain the horses so they are able to compete at that high level comfortably. On the flip side, it’s also extremely rewarding to be able to take a colicky horse that is in pain and fix them by performing the surgery they needed to survive.

What is one of the most interesting cases you have worked on?

I recently had a case where the patient was brought in for evaluation of a wound on their side, and that led to discovering a retained testicle. I also get excited when I work with any horses that I have been fangirling over in the show ring.

What is one of your favorite things about working at Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

My favorite thing about PBEC is the camaraderie and team atmosphere. I like that there are plenty of specialists to consult with, and everyone really works together well. We have a great group of intern veterinarians who make working up cases enjoyable and after-hours emergencies run smoothly.

Photo by Bridget Ness Photography

Photo courtesy of Liz Barrett.

What advice would you give someone who wants to become an equine veterinarian?

Only do it if you can’t imagine yourself doing anything else.

What is something interesting that people may not know about you?

I am a decent juggler, I hate bananas, and I have my own 13-year-old gelding that I compete in the adult jumper division when I am feeling brave enough to venture into the show ring.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC), an exceptional equine healthcare facility, will return as the Official Veterinarian of the 2022 Winter Equestrian Festival (WEF) and Adequan® Global Dressage Festival (AGDF) running through April 3, 2022, at the Palm Beach International Equestrian Center (PBIEC) and Equestrian Village in Wellington, FL. PBEC also provides Official Veterinarian services for the 2022 season at the International Polo Club Palm Beach.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is celebrating its 40th anniversary of providing top equine health care to both the year-round residents as well as horses coming for the winter season. The state-of-the-art facility is located at the intersection of Southfields and Pierson Roads in the center of Wellington, right down the road from PBIEC, the Equestrian Village, and the International Polo Club Palm Beach.

The team at Palm Beach Equine Clinic includes more than 35 veterinarians and provides expertise in almost all areas of equine health and treatment. Palm Beach Equine Clinic offers specialized sports medicine with trusted veterinarians and staff that understand the commitment it takes to care for a high-level equine competitor. The talented team offers a wide variety of services such as internal medicine, emergency care, reproduction and fertility, alternative medicine, regenerative medicine, dentistry, podiatry, and more.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic provides cutting-edge technology paired with knowledgeable and dedicated staff. The facility offers advanced diagnostic imaging with board-certified radiologists on staff as well as surgical services with three board-certified surgeons. Additionally, all primary veterinarians can refer clients to Palm Beach Equine Clinic for their innovative imaging technologies and surgical center.

In addition to the full-service equine clinic, Palm Beach Equine Clinic veterinarians will be on the showgrounds at the annex office located adjacent to the WEF stabling office on the PBIEC showgrounds. Palm Beach Equine Clinic veterinarians will be onsite daily during WEF and AGDF to assist all competing horses throughout the shows with performance evaluations, diagnostics, and treatments, as well as emergency care and standard horse care needs.

“It’s always an honor to take care of the best horses in the world that come to Wellington each winter,” said Palm Beach Equine Clinic President Dr. Scott Swerdlin. “Being on-site at the showgrounds really allows us to provide high- quality and immediate veterinary care for all of the horses competing.”

Offering exceptional knowledge, capabilities, and commitment, the team at Palm Beach Equine Clinic is thrilled to once again help equine athletes perform to the best of their abilities during the Wellington winter show season and beyond.

What To Expect After the Unexpected Strikes

Featured on Horse Network

Every owner dreads having to decide whether or not to send their horse onto the surgical table for colic surgery. For a fully-informed decision, it is important that the horse’s owner or caretaker understands what to expect throughout the recovery process.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC) veterinarian Weston Davis, DVM, DACVS, assisted by Sidney Chanutin, DVM, has an impressive success rate when it comes to colic surgeries, and the PBEC team is diligent about counseling patients’ owners on how to care for their horse post-colic surgery.

“After we determine that the patient is a strong surgical candidate, the first portion of the surgery is exploratory so we can accurately define the severity of the case,” explained Dr. Davis. “That moment is when we decide if the conditions are positive enough for us to proceed with surgery. It’s always my goal to not make a horse suffer through undue hardship if they have a poor prognosis.”

Once Dr. Davis gives the green light for surgical repair, the surgery is performed, and recovery begins immediately.

“The time period for the patient waking up in the recovery room to them standing should ideally be about 30 minutes,” continued Dr. Davis. “At PBEC, we do our best to contribute to this swift return by using a consistent anesthesia technique. Our team controls the anesthesia as lightly as we can and constantly monitors blood pressure. We administer antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-endotoxic drugs, and plasma to help combat the toxins that the horse releases during colic. Our intention in the operating room is to make sure colic surgeries are completed successfully, but also in the most time-efficient manner.”

Colic surgery recovery often depends on the type and severity of the colic. At the most basic level, colic cases can be divided into two types – large intestine colic and small intestine colic – that influence the recovery procedures and outlook.

Large intestinal colic or impaction colic is characterized by the intestine folding upon itself with several changes of direction (flexures) and diameter changes. These flexures and diameter shifts can be sites for impactions, where a firm mass of feed or foreign material blocks the intestine. Impactions can be caused by coarse feeds, dehydration, or an accumulation of foreign materials such as sand.

Small intestinal colic or displacement colic can result from gas or fluid distension that results in the intestines being buoyant and subject to movement within the gut, an obstruction of the small intestine, or twisting of the gut. In general, small intestinal colics can be more difficult than large intestinal colics when it comes to recovery from surgery.

“Many people do assume that after the colic surgery is successfully completed their horse is in the clear,” said Dr. Chanutin. “However, during the first 24 to 48 hours after colic surgery, there are many factors that have to be closely monitored.

“We battle many serious endotoxic effects,” continued Dr. Chanutin. “When the colon isn’t functioning properly, microbial toxins are released inside the body. These microbials that would normally stay in the gastrointestinal tract then cause tissue damage to other bodily systems. We also need to be cognizant of the possibility of the patient developing laminitis, a disseminated intervascular coagulation (overactive clotting of the blood), or reflux, where a blockage causes fluids to back up into the stomach.”

Stages after surgery

Immediately Post-Surgery

While 30 minutes from recumbent to standing is the best-case scenario, Dr. Davis acknowledges that once that time period passes, the surgical team must intervene by encouraging the horse to get back on its feet.

Once a horse returns to its stall in the Equine Hospital at PBEC, careful monitoring begins, including physical health evaluations, bloodwork, and often, advanced imaging. According to Dr. Davis, physical exams will be conducted at least four times per day to evaluate the incision and check for any signs of fever, laminitis, lethargy, and to ensure good hydration status. An abdominal ultrasound may be done several times per day to check the health of the gut, and a tube may be passed into the stomach to check for reflux and accumulating fluid in the stomach.

“The horse must regularly be passing manure before they can be discharged,” said Dr. Chanutin. “We work toward the horse returning to a semi-normal diet before leaving PBEC. Once they are at that point, we can be fairly confident that they will not need additional monitoring or immediate attention from us.”

Returning Home

Drs. Davis and Chanutin often recommend the use of an elastic belly band to support the horse’s incision site during transport from the clinic and while recovering at home. Different types of belly bands offer varying levels of support. Some simply provide skin protection, while others are able to support the healing of the abdominal wall.

Two Weeks Post-Surgery

At the 12-to-14-day benchmark, the sutures will be removed from the horse’s incision site. The incision site is continuously checked for signs of swelling, small hernias, and infection.

At-Home Recovery

Once the horse is home, the priority is to continue monitoring the incision and return them to a normal diet if that has not already been accomplished.

The first two weeks of recovery after the horse has returned home is spent on stall rest with free-choice water and hand grazing. After this period, the horse can spend a month being turned out in a small paddock or kept in a turn-out stall. They can eventually return to full turnout during the third month. Hand-walking and grazing is permittable during all stages of the at-home recovery process. After the horse has been home for three months, the horse is likely to be approved for riding.

Generally, when a horse reaches the six-month mark in their recovery, the risk of adverse internal complications is very low, and the horse can return to full training under saddle.

When to Call the Vet?

Decreased water intake, abnormal manure output, fever, pain, or discomfort are all signals in a horse recovering from colic surgery when a veterinarian should be consulted immediately.

Long-Term Care

Dr. Davis notes that in a large number of colic surgery cases, patients that properly progress in the first two weeks after surgery will go on to make a full recovery and successfully return to their previous level of training and competition.

Depending on the specifics of the colic, however, some considerations need to be made for long-term care. For example, if the horse had sand colic, the owner would be counseled to avoid sand and offer the horse a selenium supplement to prevent a possible relapse. In large intestinal colic cases, dietary restrictions may be recommended as a prophylactic measure. Also, horses that crib can be predisposed to epiploic foramen entrapment, which is when the bowel becomes stuck in a defect in the abdomen. This could result in another colic incident, so cribbing prevention is key.

Generally, a horse that has fully recovered from colic surgery is no less healthy than it was before the colic episode. While no one wants their horse to go through colic surgery, owners can rest easy knowing that.

“A lot of people still have a negative association with colic surgery, in particular the horse’s ability to return to its intended use after surgery,” said Dr. Davis. “It’s a common old-school mentality that after a horse undergoes colic surgery, they are never going to be useful again. For us, that situation is very much the exception rather than the rule. Most, if not all, recovered colic surgery patients we treat are fortunate to return to jumping, racing, or their intended discipline.”

Colic is every horse owner’s worst nightmare, but when the colicking patient is also pregnant, colic emergencies pose an even bigger challenge for their owner and the team of veterinarians entrusted with their care. In late February, a pregnant mare was brought to Palm Beach Equine Clinic by her owner for colic. Leading the PBEC team on this case were Drs Justin McNaughten DACT, Peter Heidmann, DACVIM, and Elizabeth Barrett, DACVS-LA. We spoke with Dr. McNaughten about the steps he and the team took to keep both the mare and foal safe.

What was the mare’s status when she was admitted to the clinic?

The presenting complaint was colic. At the time of admission, the mare had an elevated heart rate of 120 beats per minute. We then passed a nasogastric tube, which resulted in approximately 15 liters of spontaneous reflux. Once the stomach was decompressed, we proceeded with the rest of the colic work-up. As the mare was in the later stage of pregnancy, the foal occupied the majority of the abdomen. Findings on rectal palpation and abdominal ultrasound were inconclusive. The working diagnosis was ileus or decreased gut motility, but the root cause was still unknown. As part of the medical treatment, the mare had to be fasted. We started her on IV fluids with prokinetics, electrolytes, and dextrose as a source of nutritional support for the foal. Overnight, the mare remained comfortable but continued to have small amounts of reflux. The next morning, she was showing new signs of gas distension, which were not present at the time of admission. An abdominocentesis or ab-tap revealed elevations from the normal peritoneal fluid values suggesting that surgery was warranted.

What factors did you take into consideration before deciding to treat the mare?

When we are dealing with pregnant mares, we often make decisions based on the stage of pregnancy. The biggest obstacle is trying to treat the mare and doing what is safe for the foal in utero. For example, we may use different medications that are safe during one stage of pregnancy and not another, or delay procedures until after the mare delivers the foal. In this case, the owner didn’t have an ovulation date because the breeding had occurred in a paddock. A couple of diagnostic tests can be used to provide a rough estimate of the foal’s gestational age, measuring fetal orbit and the fetal aortic diameter. The results are interpreted as a rough estimate as the reference values have not been determined for each breed. Unfortunately, in the mare, gestation length does not correlate with fetal readiness or her foal’s ability to survive once it’s born. We also performed a diagnostic test to help determine fetal readiness based on evaluating the mare’s mammary secretions. In this case, we specifically measured the pH level.

Based on the mare’s need for colic surgery and the pH levels of her mammary secretions, the team of specialists discussed the options, weighing a fairly extensive list of potential risk factors for the mare and the foal. The owner was presented with the options of performing colic surgery with the foal still in utero or inducing parturition and performing colic surgery once she foaled. At the owner’s request, we induced foaling, which carries its own set of risks and can be life-threatening to both the mare and foal.

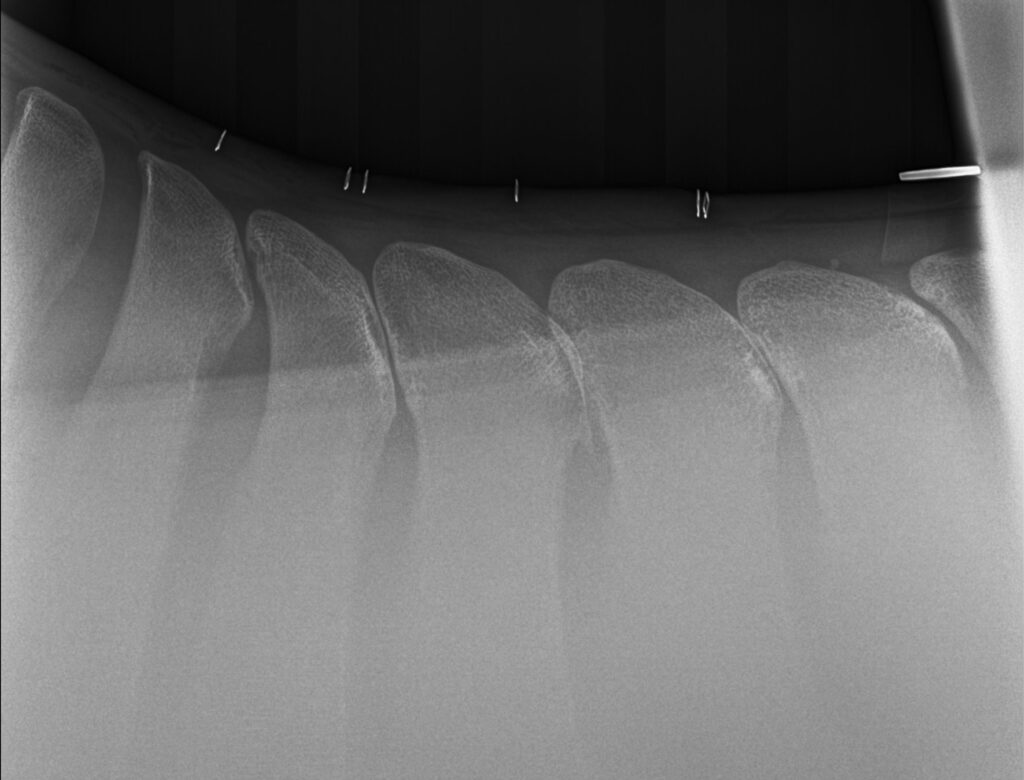

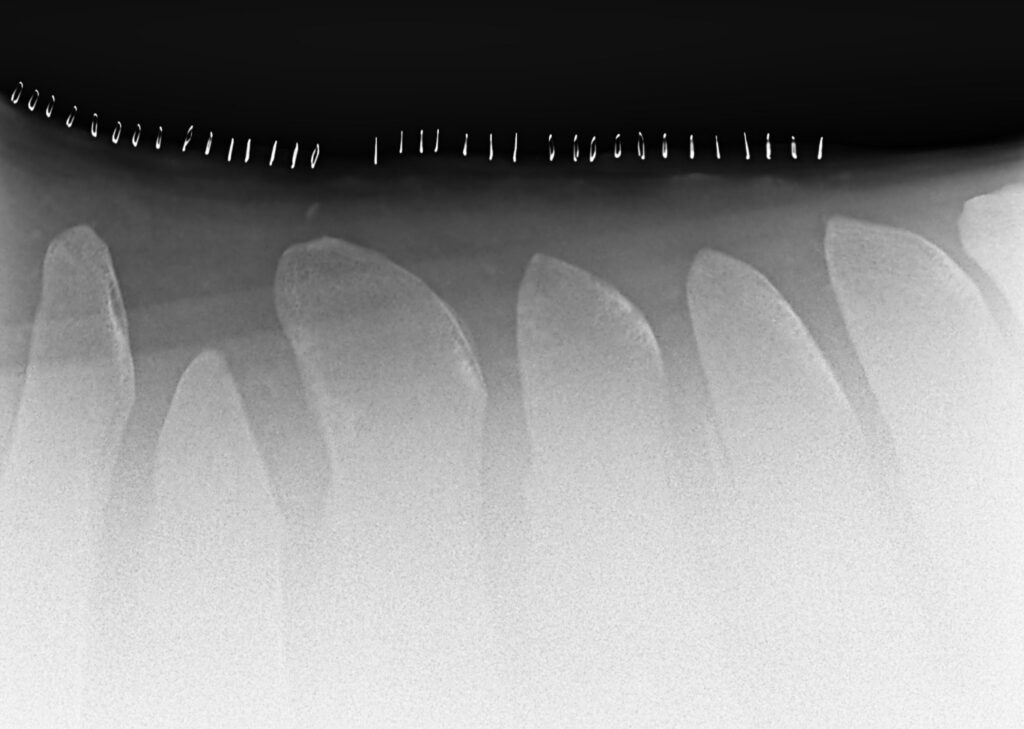

In this case, fortune was on our side. Following a successful assisted vaginal delivery, the newborn filly was hitting each of our targets for neonates. Although the filly was not showing any external signs of prematurity, we took radiographs of the knees and hocks as a precaution. The x-rays showed that the filly was a bit premature based on the incomplete ossification of the cuboidal bones, which make up the knees and hocks.

Following the delivery, the mare was then taken into surgery. During the colic surgery, Dr. Barrett identified and removed a very large fecalith, which we assumed was the root of the problem as it had the potential to obstruct the bowel. A fecalith is a hard concretion of ingested material that may increase in size and end up being a blockage in the gastrointestinal tract.

What did their postoperative care look like?

Post-surgery, the mare did very well. While hospitalized, she remained comfortable, tolerated refeeding, and displayed great maternal behavior. The filly was started on prophylactic antibiotics and given milk initially through a feeding tube until the mare had enough milk to sustain the foal. Approximately 48 hours after foaling, the filly developed signs of neonatal maladjustment syndrome, which manifests as neurologic abnormalities. One moment the foal was healthy, bright, and nursing, and the next, she was dull, listless, and disoriented. The condition subsided following IV administration of neuroprotective agents and through the use of the Madigan foal squeeze technique. The Madigan squeeze technique is a physical compression procedure that involves wrapping a foal’s upper torso with loops of soft rope and applying pressure for 20 minutes, which replicates the compression a foal experiences during birth.

Post-surgery, the mare did very well. While hospitalized, she remained comfortable, tolerated refeeding, and displayed great maternal behavior. The filly was started on prophylactic antibiotics and given milk initially through a feeding tube until the mare had enough milk to sustain the foal. Approximately 48 hours after foaling, the filly developed signs of neonatal maladjustment syndrome, which manifests as neurologic abnormalities. One moment the foal was healthy, bright, and nursing, and the next, she was dull, listless, and disoriented. The condition subsided following IV administration of neuroprotective agents and through the use of the Madigan foal squeeze technique. The Madigan squeeze technique is a physical compression procedure that involves wrapping a foal’s upper torso with loops of soft rope and applying pressure for 20 minutes, which replicates the compression a foal experiences during birth.

After a few days, both mare and foal were discharged to the care of the farm. At home, the pair were placed on stall rest followed by additional exercise restrictions allowing time for the mare’s abdominal incision to heal and the filly’s cuboidal bones to fully mature. Now, exactly one month later, I’m happy to say that both the mare and her foal are thriving.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is available 24/7 for any equine emergency and works regularly with referring veterinarians. For more information, call 561-793-1599.

For Immediate Release

Wellington, FL – March 21, 2022 – Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC) announced the addition of the innovative care program AcutePlus™ to its cutting-edge suite of client services. A long-time leader in equine veterinary care, PBEC is the first veterinary clinic in the United States to offer the service designed to help eliminate barriers to treatment and minimize risk of ownership related to veterinary care.

AcutePlus™ is a wellness-centric preventative care membership program focused on delivering excellence in horse health through preemptive treatments, essential care, and access to acute care.

“We believe that AcutePlus™ is a game-changer for horse owners,” said Palm Beach Equine Clinic President Dr. Scott Swerdlin. “With this innovative program, they can be assured that they have the ability to make the best heath care choices for their horse.”

“We are innovators at VenturePlus™,” said Ghen Sugimoto CEO of AcutePlus™. “It has been a great pleasure to work with such like-minded individuals at the top of their field at Palm Beach Equine Clinic to help them develop a program that further allows them take the very best care of their patients. AcutePlus™ puts Palm Beach Equine clients in the best position to care for their horses particularly on the worst days, when it matters the most. Additionally, we are proud to be able support Palm Beach Equine Clinic’s efforts to mentor up-and-coming veterinarians through donations from our AcutePlus Foundation™.”

PBEC will offer four tiers of AcutePlus™ membership protection to meet the level of coverage needed by each client. AcutePlus™ plans provide a range of concierge member support, customary care benefits, acute medical benefits, and mortality benefits along with exclusive member opportunities, loyalty points, and more.

Signing up is simple at AcutePlus.com.

The AcutePlus™ membership plans have two categories of benefits: customary care and acute medical care and mortality. Customary care benefits cover routine care costs like farm calls, routine vaccinations, dental floats, physical exams, microchips, complete blood counts, and Coggins tests.

Acute medical care is an important component of the extensive benefits offered through AcutePlus™. A platinum membership provides up to $10,000 per year in financial support for acute care medical bills such as surgical and non-surgical colic, choke, lacerations, eye injuries, acute onset laminitis, bowed tendons, fractured leg, and other urgent medical issues. Advanced diagnostics such as MRI and CT scan benefits are also included under the acute medical benefits portion of the plan. If the unthinkable happens and a member horse’s life is lost, AcutePlus™ can also provide up to $150,000 in equine mortality benefits.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic clients enrolled in AcutePlus™ can utilize their benefits with any licensed veterinarian anywhere in the world, not only when using PBEC’s services directly. After enrolling in AcutePlus™, when you use Palm Beach Equine Clinic for services, you maximize your benefits, and they will automatically apply a credit directly to your bill. Your membership benefits will travel with your horse around the globe, no matter how far away from Wellington you travel – extending your world-class veterinary care anywhere in the world.

Please visit AcutePlus.com for additional information or to activate your membership. Whether your horse is a competitor, a companion, or a world champion, there is an AcutePlus™ plan designed for you.

For questions regarding AcutePlus™ at Palm Beach Equine Clinic, call Dr. Scott Swerdlin at 561-793-1599.

About Palm Beach Equine Clinic

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is a full-service medical facility offering care 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Equipped with a surgical center, advanced diagnostic imaging units, laboratory, pharmacy, reproductive station and breeding shed, recovery stalls, and isolation unit, Palm Beach Equine Clinic has the necessary tools for diagnosing and treating a variety of cases. Palm Beach Equine Clinic is ideally based in the international hub of elite equestrian competition, Wellington, Florida, and is within riding distance of the Winter Equestrian Festival, Global Dressage Festival, and International Polo Club. Palm Beach Equine Clinic is proud to care for all horses, whether they are an Olympic level athlete, trusted show pony or reliable trail horse.

Visit EquineClinic.com to learn more about Palm Beach Equine Clinic and follow them on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

AcutePlus™ benefits vary by membership plan. Benefits referenced in this article reflect the AcutePlus™ Platinum Membership offered through Palm Beach Equine Clinic. Terms and conditions apply. Please visit AcutePlus.com to review all terms and conditions.

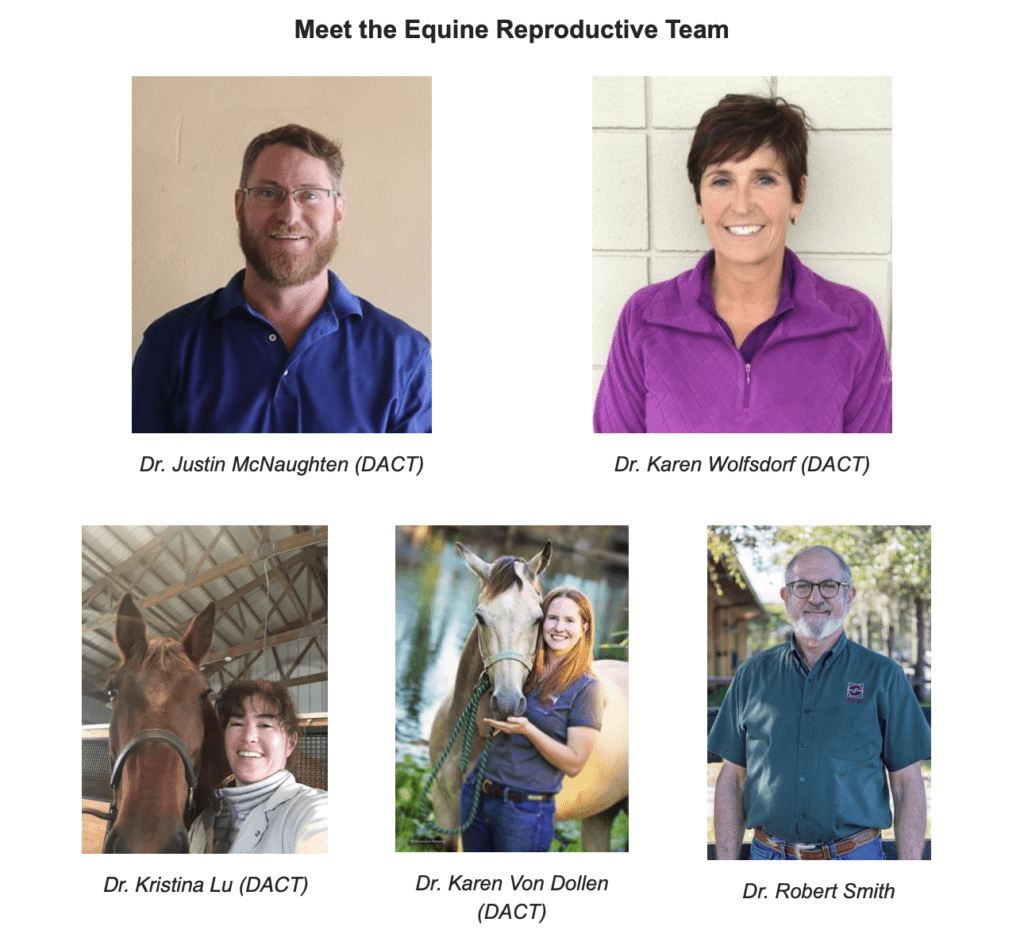

Wellington, FL – March 18, 2022 – Palm Beach Equine Clinic (PBEC) is excited to announce a new partnership with Hagyard Equine Medical Institute (HEMI), one of the leading equine medical centers in advanced reproductive medicine. Through the partnership, equine reproductive specialists will work collaboratively with the team at PBEC to expand upon the traditional services currently being offered.

While Dr. Justin McNaughten and Dr. Robert Smith will lead the team in Wellington, Dr. Karen Wolfsdorf, Dr. Karen Von Dollen and Dr. Kristina Lu from HEMI will provide assistance with advanced reproductive services. Dr. McNaughten received his BVMS from the University of Glasgow, School of Veterinary Medicine in Glasgow, UK. After completing a fellowship and residency he became a board-certified theriogenologist working in early embryonic loss, mare infertility, and stallion behavior as well as general reproduction and assisted reproductive techniques.

“It’s a new adventure using the equine reproductive specialists from HEMI to work collaboratively with Palm Beach Equine,” McNaughten commented. “The big thing is to tap into the more advanced artificial assisted reproductive techniques specifically for our sport horse and competition mares.”

Dr. Wolfsdorf emphasized that the partnership between the two clinics helps to provide a streamlined approach to their equine patients throughout the year. “Horses travel, so when they move north, to Kentucky per se, they’ll get the continued specialized care. It may not be the same individual but as a team, there will be open communication,” she explained.

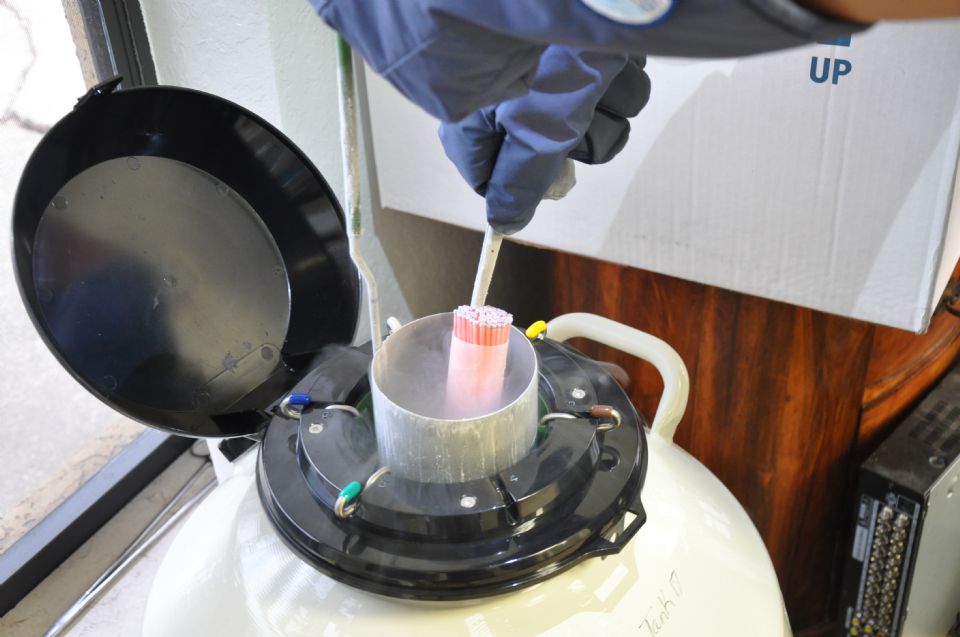

One of the advanced services that will be incorporated into PBEC’s reproduction program is Transvaginal Aspiration (TVA) of the oocyte from the mare’s ovary. Oocytes are processed and shipped to a specialized Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) laboratory. The ICSI procedure involves the micro-injection of a single sperm cell into a mature oocyte to produce an embryo. Dr. Von Dollen explained, “Oocyte aspiration offers an opportunity to salvage the reproductive potential of subfertile mares or stallions. Furthermore, embryos can be produced without the need to interrupt a mare’s competition schedule for insemination and embryo flushing,” she added.

Palm Beach Equine Clinic will offer these new advanced techniques along with all of the traditional services whether at the equine hospital or in a private barn. With expert care and advanced practices, PBEC maximizes the likelihood of a successful pregnancy and to produce the talent of the future.

To learn more about the routine and advanced reproductive services offered this season contact PBEC at 561-793-1599, HEMI 859-255-8741 or visit www.EquineClinic.com or www.Hagyard.com. Follow Palm Beach Equine Clinic and Hagyard Equine Medical Institute on Facebook and Instagram to see more about the clinic, its vets, and those they serve.