Tag: internal medicine

On March 24, 2021, board-certified internal medicine specialist Dr. Peter Heidmann answered questions regarding Equine Herpesvirus (EHV) live on the Noelle Floyd Instagram page. Watch the video below or read these six main takeaways he discussed.

1. Equine Herpesvirus (EHV) can be present in any area where there are horses.

EHV can be found in horses in every country around the world. The virus can have varying consequences and not every horse may be symptomatic. The duration of their immunity, their capability to shed viral particles, and whether they continue to carry the virus are all variables unique to the individual horse.

2. There are multiple strains of EHV that lead to varying health defects.

Most horses, by two years old, have been exposed to EHV. Nearly every horse over five years old has had EHV in a mild respiratory form, in which they have likely suffered from symptoms such as a runny nose or cough. The disease becomes gravely serious when there is a neurological form of EHV-1 that is spreading rapidly among horses.

Over the last century, the primary focus of EHV disease control was related to reproduction. EHV was a major cause of infectious abortions in mares. Since the advent of effective vaccines that protect against EHV abortions, the concern has shifted to the rare but serious occurrences of neurologic disease caused by EHV-1.

Certain strains of EHV can have more propensity to cause neurological disease, while others do not. It is important to understand that both “neurologic” and “non-neurologic” strains can cause neuro symptoms, and that some horses infected with “non-neurologic” strains may also develop the neurologic form of the disease. Symptoms of mild neurologic disease can include ataxia or hind end weakness and irregular gaits. When horses suffer mild neurologic symptoms, most will make a full recovery. If they suffer from severe symptoms, it can be increasingly difficult to treat, and some cases can be fatal.

3. Vaccination is key.

There are currently no genetic explanations regarding whether a particular horse may be more likely to contract EHV-1. However, when a horse is stressed, whether it be from shipping, competing, or other causes, its immune system is more susceptible to illness. EHV-1 can live in the central nervous system, and during times of stress when endogenous corticoids are produced, the virus can start to replicate. This causes the horse to shed viral particles into the environment and explains why there are outbreaks of the disease. It does not take much for a stressed horse to start shedding viral particles into the environment and infecting non-stressed horses nearby.

Vaccinations can help horses generate additional antibodies and minimize the spread of disease. The vaccines available today are effective at preventing the respiratory and reproductive strains of EHV, but are not effective for the neurologic strain. It is just as important as ever to vaccinate because vaccines help to limit the spread of virus by decreasing the shedding of viral particles from each individual horse.

Immunization is recommended every six months at a minimum. Most vaccine manufacturers suggest vaccinating against EHV as often as once every 90 days when travelling or competing. It is recommended to work closely with your veterinarian to tailor a vaccination program for your horses’ specific requirements.

4. Surveillance is crucial to preventing a serious outbreak in the United States.

Due to the recent outbreak in Europe, medical surveillance has increased. There are now extra layers of protection in the process of importing horses. Imported horses have always been quarantined, but now horses are also receiving a nasal swab to look for the presence of EHV-1 in their nasal passages. There have been cases of EHV-1 in the U.S. recently. However, there is no evidence that these EHV-1 cases are related to the major outbreak in Europe, partially thanks to our increased level of surveillance on horses being brought into the country.

5. The handling of horses with fevers shifts dramatically when cases have been identified locally.

Veterinarians have significantly shifted how show horses with any symptoms are being handled. If a horse had presented with a fever or runny nose prior to the European EHV-1 outbreak in early 2021, it would typically have been treated by its own veterinarian and left to return to full health. What is happening now is that each horse with a fever becomes a possible candidate for being the index case of EHV-1. This changes veterinarians’ responsibilities everywhere because of the potential for the disease to spread among the population in respective local areas. Horses with fevers must therefore be strictly quarantined and tested.

The fastest and most accurate test in the world for diagnosing EHV-1 is a PCR test, which looks for the DNA of the infecting organism. The horse will test positive if it is actively shedding organisms. The biggest downside is that it typically takes 24 hours to produce results. Therefore, horses who have been tested are put under strict isolation until the test results come back. Often, by the time test results are ready, the horse’s symptoms have ceased. Yet that is the level of scrutiny necessary to prevent a serious outbreak.

6. There are clusters of the disease reported all over the Unites States, although they are unrelated to the neurological strain of EHV-1 outbreak in Europe.

While this is routine from a veterinarian’s perspective, it is still serious and certainly worth our attention. A few isolated cases reported in the U.S. this March have been found to be due to the neurotropic form of the disease and some have been non-neurotropic. The concern is warranted, but cases are highly localized, mainly in areas with large equine populations. We see the disease cropping up because the virus may already be dormant in their bodies. To minimize the likelihood of outbreaks on the individual farm level, have a vaccination program with your veterinarian and if necessary take temperatures of horses twice daily to catch any viral infection early.

For up-to-date information on reported cases of EHV, horse owners can utilize the following resources:

- Disease outbreak alerts via the Equine Disease Communication Center

- FEI website for notices and updates on international competition protocols

- Your state’s Department of Agriculture website for reportable diseases in your area

Anyone who has experience with horses is aware of the very real threat of losing a horse to colic or other gastrointestinal disease. But looking back on the history of equine death causes, colic still holds the same percentage as it did 20 years ago, standing firm as the second highest cause of death behind natural causes. Why hasn’t modern medicine decreased the chance of losing horses to colic? Why do we all still share the common fear of our horses colicking out of the blue, with little warning and minimal reliable strategies to prevent problems?

The answers to these questions remain a work-in-progress, but over the past 10 years, veterinarians and researchers have learned a lot about the role of the equine gut microbiome on all sorts of health outcomes, including colic, maldigestion, dysbiosis, and a myriad of other health problems.

The equine gut microbiome is an ecosystem composed of quadrillions of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and even viruses, which interact and coexist in the gastrointestinal tract and contribute to overall gut health and well-being. In equines, when the microbiome is disrupted in such a way that populations of beneficial bacteria and yeast have declined and/or populations of harmful pathogenic bacteria and yeast have increased, it is not unusual to see issues such as colic and colitis, laminitis, among other serious conditions.

Like each individual horse, each microbiome is unique; regional, dietary, and even breed and genetic differences can create diverse microbiomes, and varying degrees of digestive health. Even within one horse’s microbiome, the “top end” of the colon can be drastically different from the “bottom end” in terms of the population and diversity of microbes. The way all the organisms perform and act within the microbiome determines the functionality of the gut as a whole. Board-certified internal medicine specialist Dr. Peter Heidmann leads the Internal Medicine department at Palm Beach Equine Clinic and takes us on a deeper dive into the equine gut microbiome.

Microbiome and Nutrition

“When we’re working to improve overall GI health, we are basically trying to increase the population of ‘good bugs’ and crowd out the ‘bad bugs,” Dr. Heidmann remarked. The combination of probiotics, prebiotics, and diet are all key factors that influence what happens on the inside of a horse’s gut. According to Dr. Heidmann, a well-balanced diet is most important, but the sources of nutrients also play a huge role in promoting gastrointestinal health.

“Probiotics can limit lactic acid production and prevent huge swings in pH in the cecum. This happens through many pathways, but largely by encouraging fiber fermenters over bacteria that like to gobble sugars and produce lactic acid,” he said. “Prebiotics provide additional, non-starch nutrients and are meant to support healthy flora, or microbes. Prebiotics also limit the likelihood and severity of dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, when the diet changes, like what can happen following sudden exposure to too much starch-rich feed.”

Excessive amounts of starch-rich grains can reduce populations of healthy flora, decrease the types of bacteria that are present in the colon, and also promote overgrowth of unhealthy flora. In turn, overly homogenous populations limit a horse’s resilience to stress, dietary changes, and other unpredictable changes such as those in weather.

Oats and other starch-rich grains cause increases in propionic acid-producing bacteria, while hay-only diets increase acetic acid-producing flora, and therefore promote more diverse and stable populations of beneficial bacteria and yeasts. On the flipside, feeding hay and no grain means the nutrients are being digested much more slowly and will promote more diversity and stability of flora populations.

“At the same time, some ‘good’ bugs are also decreased when a hay-only diet is fed, especially ones that rely on easy-to-digest starchy grains,” noted Dr. Heidmann. “One type of organism, the Lachnospiraceae, is among the most prevalent type present in a healthy horse’s hindgut, and its population also diminishes when grain is not being fed.”

Ultimately, some easily digestible concentrate feeds promote healthy bacterial populations and release lots of energy quickly, yet it is fairly easy and risky to over-do the easily digestible feed. Not only do abrupt changes in diet increase the risk of upsetting a horse’s healthy microbiome, but feeds that are high in carbohydrates can also promote gas formation, lactic acidosis, and other types of colic. “Simply put, garbage in equals garbage out,” Dr. Heidmann explained.

Other Stressors to the Microbiome

Aside from what goes into the horse, there are other factors that determine the behavior of the microbiome and the overall functionality of the gut. Genetic makeup almost certainly plays a role in the way organisms manage the nutrients going in and, in turn, impacts the horse. Stress is another significant factor that definitely has a relationship with the gut, though it remains difficult to draw clear lines of “cause and effect” when studying all the ways that stress affects a horse’s gut health.

It is common knowledge among trainers that horses with anxious, “stressed-out” personalities seem prone to developing stomach ulcers. Separate from stress caused by riding, changes in surroundings, or even changing stablemates can make a difference in the organisms in a horse’s gut. Even when the feeding program remains consistent, a change in workload or their neighboring stall-mate invites stress and can promote ulcers.

“There is reason to believe that colon ulcers indicate problems in the gut microbiome,” said Dr. Heidmann. “Organisms, both healthy and not, vary between different barns, even in the same region or town, and those differences are also associated with differences in a horse’s microbiome. Even if horses are on the exact same food, with the same hay and turnout schedule, the flora is going to be different due to varying exposure to new microorganisms.” But this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t subject our horses to change. Many competition horses are accustomed to changes in environment and can perform without major gastrointestinal issues. The primary goal is to maintain as much consistency as possible when horses go through geographical changes that may disrupt their gut health.

“The relationship between stress and gut health isn’t as simple as a cause-and-effect relationship, where stress leads to a direct change in the behavior of the bugs, or where a change in flora directly increases a horse’s stress levels. It is a complex, dynamic interaction; it’s a constant feedback loop.”

Dr. Heidmann

It is difficult enough to separate cause from effect when looking at the relationships between gastrointestinal flora and factors like diet, exercise, pre- and probiotics, or supplemental digestive enzymes. But explaining the relationship between horse’s behavior and their GI flora is inherently subjective, and therefore even more difficult to confirm.

“It may seem far-fetched to think that a horse’s behavior might be affected by the balance of flora in their GI tract, but some microbes appear to have developed mechanisms that encourage certain behaviors by producing compounds that mimic the horse’s own neurotransmitters,” reflected Dr. Heidmann. “This can translate into increasing hunger signals or stimulating cravings for certain foods. Some microbes can enhance taste sensation, and others can co-opt a horse’s normal signaling pathways to enhance mood or increase discomfort by slowing gastrointestinal motility. Any or all of these mechanisms may be up or down regulated during changes in the balance of GI flora.”

Still More to Learn

Veterinary science and research still have a long way to go to draw firm associations between illness and the microbiome. According to Dr. Heidmann, “it’s not known yet if the disease is the cause of the change in microbiome flora or if it is the result of a change in the flora, but for sure there is a strong relationship between these things. For now, we don’t yet know if the horse has an unusual balance of organisms because of its problems with chronic colic, or if it is the reverse: that the colic is rooted in an unusual balance of GI organisms.”

With today’s modern scientific tools and research methods, we are closer than we’ve ever been to understanding the dynamics between microbiome and overall health. Comprehensive understanding of the interplay between diet and digestion, between the microbiome and behavior, and between food and flora remains a work-in-progress, but ongoing studies promise to shed light on our current understanding.

In the interim, a consistent regime of diet and exercise, with workload tailored to each horse’s skillset and stage of training, remain the best ways to minimize risk and promote healthy GI flora. “Prebiotics and probiotics and other micronutrients are sometimes necessary,” said Dr. Heidmann, “but the most important things remain hay and sunshine, water and exercise, and consistency most of all.”

Appointment Request

Please fill out this form and our staff will contact you to confirm an appointment.

Identifying the root of performance issues in equine athletes can be like connecting a puzzle of often-ambiguous signs, or a process of elimination through diagnostics. Veterinarians can exhaust all the tools in their medical arsenal trying to figure out why a horse may be losing muscle mass and stamina or refusing to work, but the answer could be hiding in the horse’s muscle tissue. Palm Beach Equine Clinic’s Internal Medicine Specialist Peter Heidmann, DVM, DACVIM, has a keen interest in connecting these signs and identifying muscle disorders.

“Correctly diagnosing and treating muscle disorders in horses can be a very rewarding process, because once you develop an effective treatment plan, the horse will usually experience an extraordinary recovery. I’ve had cases where we sent muscle biopsy samples to a pathologist, enacted a treatment plan, and then sent another sample six months later to check our progress. The results were so impressive that the pathologist called to confirm that it was the same horse!”

Dr. Heidmann

Muscle disorders can present with a range of signs from muscle stiffness and pain to extreme cases of muscle atrophy. Most commonly, presentations occur during training and may include pain, stiffness, tremors, and a reluctance to move. Such symptoms usually lead veterinarians to conduct a full lameness evaluation.

“We usually look at mechanics first, and when there is no lameness determined and no joint, tendon, or ligament issues, we can further narrow down the search to determine if there is nerve impingement leading to muscle atrophy,” said Dr. Heidmann, who will often see a horse with such impingement work very well at an extended trot, but lose all power or appear stiff and lame as soon as the gait is collected.

To confirm a horse’s neuromuscular health and proper function, Dr. Heidmann will first run a blood panel to test for abnormal elevations in two enzymes. The first is serum creatine kinase (CK), which is released within just a few hours of muscle damage. Elevations in CK are usually consistent with training, transport, or taxing exercise. The second is serum aspartate transaminase (AST), which is an enzyme that rises more slowly after muscle injury, and can provide a veterinarian with knowledge about the body’s longer-term response.

“If you think of muscle cells as little balloons, once you pop one, CK and AST are released into the blood,” said Dr. Heidmann. “When these numbers are high, we know we have way too many balloons popping all at the same time. Then we just have to figure out why.”

Neuromuscular Biopsies Leading to Diagnoses

The diagnosis of a particular neuromuscular disorder can be challenging, since many of the symptoms are the same, regardless of the underlying disease. After blood testing, neuromuscular disorders can be diagnosed using a muscle biopsy. This minimally invasive, but highly revealing procedure is one that Dr. Heidmann turns to often in order to not only diagnose, but to also provide life and career-saving treatments.

“I usually use a Bergstrom needle, which is used to collect the sample through a tiny site in the horse’s skin. The muscle tissue then falls into a slot in the needle, and is removed to be examined under a microscope,” said Dr. Heidmann, who also says the most common locations for collecting muscle biopsies, depending on the symptoms, include the triceps, top line, hamstring, gluteal muscle, and tail head of a horse. “You can physically see some of the things that aren’t functioning properly even if the enzymes aren’t high.

“The beauty of a muscle biopsy is that you are looking at where the nerves come into the muscle, so you can detect abnormal nerve supply to an area while leaving the horse with nothing more than a nick in the skin,” he continued. “Once we see the muscle tissue, we can tell if the horse requires nutritional changes, injections, or other treatments. Non-invasive nerve stimulation is what the future holds for the treatment of many muscle disorders, but it is still an evolving treatment in veterinary medicine right now.”

Once the muscle biopsy is collected, Dr. Heidmann can go to work identifying the problem while the horse immediately returns to work. Non-invasive diagnostics and treatments are the wave of the future in both human and equine medicine. For Dr. Heidmann, neuromuscular biopsies are helping him to look below the surface of a horse’s skin to evaluate, diagnose, and provide treatments without making a single cut.

Learn more about Equine Internal Medicine by clicking here.

Appointment Request

Please fill out this form and our staff will contact you to confirm an appointment.

To Address Raised Concerns

The spread of the novel coronavirus has raised serious concerns as the status of the virus continues to evolve. As equine veterinarians, Palm Beach Equine Clinic is here to clarify questions raised regarding the potential impact of this disease in the equine industry.

Coronaviruses include a large group of RNA viruses that cause respiratory and enteric symptoms and have been reported in domestic and wild animals. Equine Enteric Coronavirus and COVID-19 are both coronaviruses, however, they are distinctly different viruses.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), infectious disease experts, and multiple international and national human and animal health organizations have stated that at this time there is NO EVIDENCE to indicate that horses could contract COVID-19 or that horses would be able to spread the disease to other animals or humans. Equine enteric coronavirus and COVID-19 are NOT the same strains and there is no indication that either are transmissible between species.

Therefore, it is important to concentrate on the health of our equestrians by being precautious and following recommendations from public health officials. Palm Beach Equine Clinic will continue to make every effort to stay informed of developments with COVID-19, and will continue to provide veterinary care to all horses regardless of the status of this disease.

A Profile of Equine Enteric Coronavirus

Equine coronavirus is an enteric, or gastrointestinal, disease in the horse. There is NO EVIDENCE that equine enteric coronavirus poses a threat to humans or other species of animals.

- Transmission: Equine coronavirus is transmitted between horses when manure from an infected horse is ingested by another horse (fecal-oral transmission), or if a horse makes oral contact with items or surfaces that have been contaminated with infected manure.

- Common Clinical Signs: Typically mild signs that may include anorexia, lethargy, fever, colic or diarrhea.

- Diagnosis: Veterinarians diagnose equine enteric coronavirus by testing fecal samples, and the frequency of this disease is low.

- Treatment and Prevention: If diagnosed, treatment is supportive care, such as fluid therapy and anti-inflammatories, and establishing good biosecurity precautions of quarantining the infected horse. Keeping facilities as clean as possible by properly disposing of manure will help decrease the chances of horses contracting the virus.

Information for this notice was compiled using the following sources:

Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center: https://www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center/veterinary-support/disease-information/equine-enteric-coronavirus

American Association of Equine Practitioners, Equine Disease Communication Center: https://aaep.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Outside%20Linked%20Documents/DiseaseFactsheet_Coronavirus.pdf

Internal Medicine: What’s it all about?

Palm Beach Equine Clinic President Dr. Scott Swerdlin often says, “If you want to attract equine veterinary specialists, you have to have impressive facilities and technology in place.” Palm Beach Equine Clinic is one of the few veterinary clinics in the country to offer clients the talents of board-certified specialists in nearly every branch of equine veterinary medicine. One such specialist is Peter Heidmann, DVM, DACVIM, a graduate of Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine, who joined Palm Beach Equine Clinic in 2016.

Dr. Heidmann specializes in the treatment of internal medicine cases at Palm Beach Equine Clinic.

What attracted him? The facilities! In the heart of South Florida’s horse country and at the center of the busiest winter competition schedule in the world, Palm Beach Equine Clinic boasts an internal medicine and infectious disease center at its Wellington-based clinic.

The crown jewel of the center is the ability to stop airborne disease dead in its tracks with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved isolation stalls that completely enclose horses in their own environment with individual filtered airflow systems that do not reach other horses. On top of secure isolation and individual airflow systems in their internal medicine facilities, Palm Beach Equine Clinic also constructed areas for each stall where medications are prepared, equipment is stored, and dirty bedding is handled.

To further mitigate risk, veterinarians, technicians, and staff take every available precaution, including foot baths before entering the stalls and wearing personal protective equipment such as Tyvek suits, gowns, and face masks to provide multiple layers of protection against spreading disease. In some cases, a specific team of doctor, technician, and intern is assigned to a patient and won’t touch another horse for the duration of the treatment.

Accurately Diagnosing Internal Medicine Cases

Diagnostics is not a guessing game at Palm Beach Equine Clinic. With advanced imaging equipment, including a computed tomography (CT) machine, standing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and nuclear scintigraphy camera (bone scan), as well as radiography (x-ray) and ultrasonography capabilities, Palm Beach Equine Clinic is armed and ready to quickly and accurately diagnose internal medicine cases.

Dr. Heidmann refers to the facilities and his work at Palm Beach Equine Clinic as a luxury, saying, “I’ve managed many cases in various facilities going all the way back through internship, fellowship, and residency, but this is as nice as any place I have ever worked. It makes the risk to the horses so much lower, but also removes the anxiety for myself because I’m able to look a client in the eye and tell them that there is no risk. I don’t have a concern about disease spreading from one patient to another because at Palm Beach Equine Clinic we have the tools that we need.”

Understanding Internal Medicine

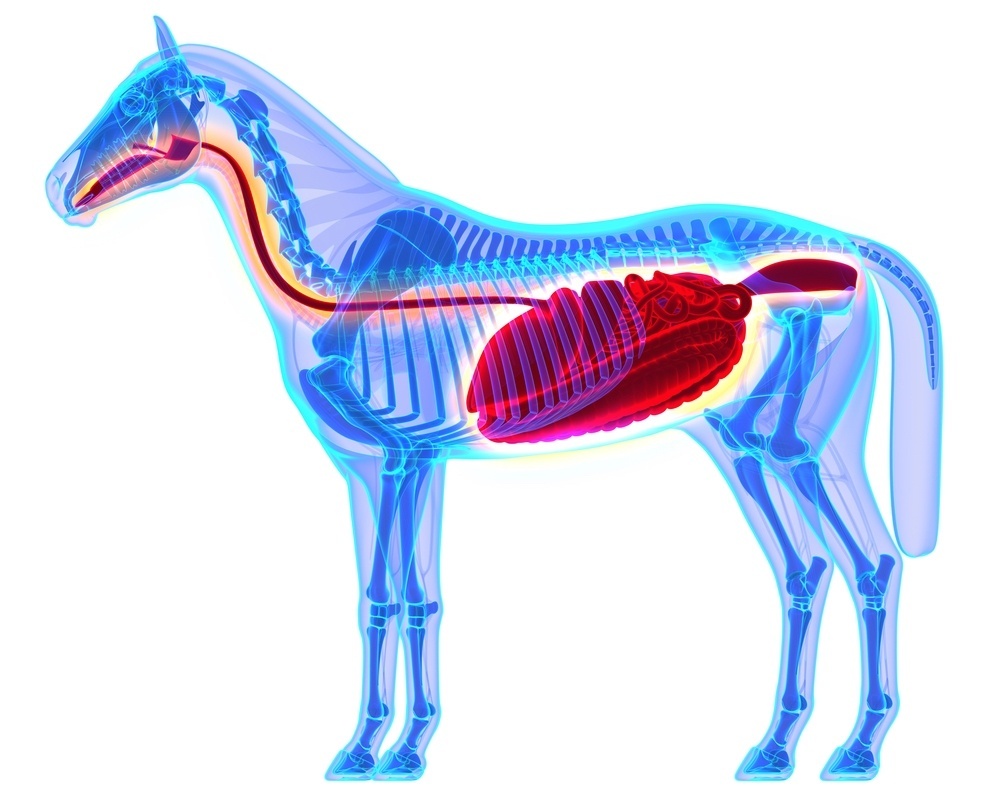

To understand how diagnostic tools are most effective, one must understand what exactly internal medicine is. In an effort to define internal medicine, Dr. Heidmann noted, “What you’ll see on the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) website is an emphasis on organ systems and organ system problems – respiratory disease, gastrointestinal disease, and neurologic disease being three of the most prevalent.

“What it really entails is a way of analyzing problems specific to the organ systems,” he continued. “It can be all over the map, and that’s part of what makes the specialty so fun and interesting.”

The most common internal medicine cases can be split into three categories:

- gastrointestinal (GI) problems

- neurological system issues

- respiratory diseases.

Gastro-Intestinal Problems in Horses

“When it comes to GI issues, I usually see horses in two categories,” said Dr. Heidmann. “Number one are the horses that may need to go to colic surgery and the horses that just had colic surgery. The other is horses with intestinal infections, often colitis in which they have heavy diarrhea.”

According to Dr. Heidmann, all of the treatments for colitis tend to boil down to the same thing: replacing their ongoing losses and letting the intestine heal itself. It doesn’t matter if it’s colostrum, salmonella, Potomac Horse Fever, or any other kind of infection.

Equine Neurologic System

The nervous system in a horse is made up of the brain, spinal cord, and several different kinds of nerves that are found throughout the body. These create complex circuits through which animals experience and respond to sensations. Unfortunately, many different types of diseases can affect the nervous system, including birth defects, infections, inflammatory conditions, poisoning, metabolic disorders, nutritional disorders, injuries, degenerative diseases, or cancer.

“Palm Beach Equine Clinic has an incredible ability to do advanced imaging and diagnostics on neurologic conditions,” said Dr. Heidmann. “With equipment like the standing CT, we can do scans of the head and neck with contrast – a CT myelogram – which really increases our ability to diagnosis a condition.”

Palm Beach Equine Clinic is able to locate problems not only on the top or bottom of a horse’s neck, but also on the sides of the neck – an area previously inaccessible to view even from myelograms under anesthesia.

“That’s part of the satisfaction of the job that I do; It’s not just ‘here is my experience and here is what I guess is going on.’ I have all of these options at my fingertips for diagnostics and tests. We can confidently confirm our clinical suspicions and then do treatment based on that.”

Respiratory Disease in Horses

As common as a cold for a human or acute in nature, Dr. Heidmann further breaks down the different kinds of common respiratory disease in horses into three categories:

One of the repeatedly praised and recognized characteristics of Palm Beach Equine Clinic is the great pool of talented professionals from all specialties that make up the large team. In 2016, Dr. Peter Heidmann, DVM, MPH, began working with Palm Beach Equine Clinic for the winter season, and this year, the accomplished internal medicine specialist is returning to work with Palm Beach Equine Clinic for the duration of the 2018 winter season.

Dr. Heidmann graduated from Tufts University with his veterinary degree in 2000 before beginning a one-year internship in equine medicine and surgery at Arizona Equine, followed by a one-year surgical fellowship at Oregon State University, followed by a residency for internal medicine at the University of California, Davis, which he completed from 2002 to 2005. In 2005, Dr. Heidmann joined a private equine practice in Montana, and today he is the owner and hospital director of Montana Equine.

Q: What prompted you to pursue equine veterinary medicine?

I knew I wanted to be a vet for a long time, but I didn’t know that I wanted to practice more individually focused medicine until I was going through vet school. It wasn’t until my fourth year, where you’re actually starting to work with patients, that I made that realization. I started moving in that direction, and I had some faculty that saw the same for me and encouraged me to do the horse stuff. I always loved working with horses, but up until that time, I thought my background was too agricultural to do high-end sport horse work. But their encouragement helped me realize that wasn’t true. Then, I decided as a result of that realization and thought process, that I wanted to do an internship and residency to become specialized in internal medicine.

Q: What led you to Montana, and how has your role and practice evolved from when you started there in 2015 to today where you’re now the owner and hospital director of Montana Equine?

When I finished my residency at Davis in 2005, I wanted to be in the west. I wanted to be somewhere where there was nobody with my skill set – meaning internal medicine. I wanted to be in a small mountain town basically. Somewhere that I could practice the kind of medicine that I was trained to do but not in big metropolis. So, I narrowed it down to a practice in New Mexico and a practice in Montana. I went to work for a practice in Bozeman, MT, in July of 2005 and six months later my predecessor, Dr. Dave Catlin, passed away in a car crash. It was really sad. He had three kids, left a widow, and it was his dream to start an equine only specialty vet hospital, which he had done in 1999.

When he died, the conventional wisdom around Bozeman was, ‘Well this can’t be done. Dave had a dream, and it’s not a realizable dream now. There aren’t enough people here. Montana residents won’t understand specialized medicine and they won’t pay for it.’ I was faced with this proposition of leaving the practice after just arriving there, but I knew that was where I really wanted to be. I basically picked up the pieces of Dr. Catlin’s practice and formed Montana Equine in February of 2006.

Now we have a 7,500 square foot hospital with a surgery site at Bozeman, and I have a partner there, an associate, and two interns. We have two satellite locations: an ambulatory-only satellite in Helena, MT, and have nearly completed satellite clinic building in Billings, MT, which is the largest community in Montana.

Q: You began working with Palm Beach Equine Clinic during the 2016 Winter Equestrian Festival (WEF) season, but you’re out in Montana and have your own practice there. How did that relationship come about, and what does it look like today?

There are various aspects to that. We’re very quiet in Montana from basically Thanksgiving through March, and it’s not really my personality to sit around. That’s one aspect, and another is from a business perspective, it allows me to bring more vets on and keep them year-round. A third element is the desire to do more high-end medicine, and a fourth element that led me to Wellington, is my wife, Allison, who is a professional jumper rider. Two years ago, during the winter of 2015, Allison had a girlfriend who had just had a baby and asked Allison to run her business for her here at WEF. I thought that was an interesting idea and started talking to Palm Beach Equine Clinic and found that there might be a need for an internal medicine specialist in their group. So that’s when I started coming. At that point, I was in Wellington for four or five days and then home for ten days, back and forth and back and forth. Then last year, I was more of a week here and a week at home. We had our first child, so Allison and Oliver, who was brand new then, were here straight through, but I went back home to Montana as well. The need is there and the relationship is great. So, this year, I’m in Wellington full-time for the WEF.

Q: What do you enjoy most about having the opportunity to practice with Palm Beach Equine Clinic?

It’s a huge group of people, so there are a lot of personalities. When you have a lot of different personalities, you have a lot of different perspectives on treatments, and that’s interesting and fun. It means that every year when I’m here, it’s pretty dynamic. Back in Bozeman, I have a great team, but I’m the leader of the team. I’m the oldest and the most experienced. That’s good, and that’s not to say that those guys don’t definitely come with new ideas, but being here, there are so many ways of doing things that I end up picking up new tricks or new ideas even though I’ve been practicing for most of two decades. So here at Palm Beach Equine Clinic, I’m picking up new strategies and new techniques separate from new stuff coming out in the world – just different ways of doing things, and different experienced veterinarians to bounce ideas off of. That’s really refreshing and stimulating.

From a vet’s perspective, with the Wellington demographic there is sometimes less of a limitation on budget and expense, so we’re really able to set that factor and worry aside and instead focus solely on what is best for the patient. The limitation isn’t financial; the limitation is just medicine and what we are able to do, which is exciting and allows us to see great results.

Q: Have you had any favorite cases or standout moments during your time with Palm Beach Equine Clinic thus far?

I won’t name any in particular, but what I really enjoy are the challenging medical cases, the internal medicine cases that tend to be really sick and that you’re able to fix. The most common ones that we see are probably sickness after colic surgery, horses with really bad diarrhea, so colitis cases, followed by foals. Those cases generally all have a lot of things going on in a lot of different organ systems. So, there are a lot of factors to balance. Internal medicine people like me are kind of inherently nerdy, and we really get into what’s happening with the acid-base status, electrolytes, blood gases, fluid volumes, and other technical aspects of horse medicine.

Q: What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

While in South Florida, we’re basically working all the time, so not as much here except trying to get exercise and be fit. I like to ride a bike or go for a run. At home, the Gallatin Valley – which is where Bozeman is – is surrounded all around by mountains. The valley floor at Bozeman is at about 5,000 feet, and the peaks are at 8,500, so you can do a lot of really serious hiking. Our son is only 18 months old, but he loves it. I’ve had dogs in the past where their whole personality changes when you get out of town, and that’s what Oliver is like too. It’s almost like his whole face is a different face when he’s out there.

Diarrhea can be a common problem for horse owners, but how do we know when it is serious? What are some of the causes? How do we treat severe cases and what potential complications you should watch for? Internal Medicine Specialist Dr. Peter Heidmann of Palm Beach Equine Clinic in Wellington, FL, has the answers to these questions and more.

Diarrhea, defined as loose stools, or excessive and overly-frequent defecation, occurs when the intestine does not complete absorption of electrolytes and water. Simple changes in feed, exposure to lush grass, or a bite of moldy hay can cause brief irritation of the bowel, giving a horse diarrhea for a day or two, but anything more than that could be from a variety of more serious causes. Bacteria, viruses, and toxins are all factors that can damage the lining of the bowel and lead to equine diarrhea and other complications.

Causes of Equine Diarrhea

The organisms that cause equine diarrhea are mostly bacteria –Salmonella and Clostridium difficile are among the most common. Clostridium difficile is associated with antibiotic use in both people and horses. While antibiotics are useful to kill bad bacteria, they can also kill good bacteria at the same time, upsetting the balance of flora in the body. If a horse goes on antibiotics for any reason, such as a wound or an infection, that can upset the good bacteria in the intestines and cause bad bacteria, such as Clostridium difficile, to grow.

Clostridium difficile can be found naturally in the environment. There are various types of Salmonella, most adapted to birds or to cattle or other livestock, so horses that are around livestock have a higher rate of becoming infected with that particular bacteria. Horses can also carry Salmonella and not have any symptoms, so they can pass it to each other. If the healthy flora in the horse’s body is thrown off by even a small change in diet, or something bigger like a colic episode, or antibiotics, then Salmonella can grow up in its place.

Another bacterial cause of equine diarrhea can be a disease called Potomac Horse Fever. A bacteria called Neorickettsia risticii, which is carried by snails and conveyed by flies like caddis flies, causes Potomac Horse Fever. For this reason, horses that live near rivers or streams can become infected. During warm weather months, caddis flies pick up the bacteria from the streams and can transfer the disease to nearby horses that accidentally eat the flies or larvae. There are hotbeds for Potomac Horse Fever throughout the U.S., including the Potomac basin where it was first described, as well as many parts of the East Coast, and areas of Oregon, northern California, and Montana.

A viral cause of equine diarrhea commonly seen is Coronavirus. This gastrointestinal virus shreds the intestinal lining and can cause horses to become very sick. The body has to reline the bowel, and it does so quickly, but it takes three to five days, during which the horse may have severe diarrhea and secondary infections.

“Coronavirus was thought for a long time to just be an opportunistic infection and that the virus would take advantage of the horse already being sick, but now it is more and more believed to be the cause of its own type of disease,” Dr. Heidmann stated. “Like all of these diseases, it causes damage to the lining of the bowel and supportive care must be used to help the horse heal. Unlike bacterial infections, however, you cannot directly treat the organism, since there aren’t appropriate drugs to directly treat coronavirus in horses.”

Outside of the infectious causes of equine diarrhea, there are mechanical causes, such as ingestion of sand, which can be a common problem in locations like South Florida. Sand is irritating to the lining of the bowel and can cause damage from its weight, as well as its abrasiveness. In general, sand is irritating enough that the body cannot retain the fluid that it needs in the intestines. As a result, it will cause secretory diarrhea where too much water is being lost. Clearing the sand usually solves the problem and the bowel is then able to reestablish a healthy lining.

A final cause of diarrhea in horses is toxins. Toxic plants, such as Oleander, can be fatal in large doses, but if ingested in small amounts, can be a severe irritant to the bowel. Other toxins that a horse can ingest in the environment, such as phosphate or insecticides, may also cause diarrhea.

Treatment for Equine Diarrhea

The single most important treatment for diarrhea, no matter the cause, is supportive care. Supportive care includes providing intravenous fluids to replace the fluids lost, providing protein in the form of plasma for the protein lost due to lack of absorption, as well as balancing electrolytes.

The next most important step is taking measures to either reestablish good flora within the gut or to remove the bad bacteria. In the past, a powdered charcoal was used, which is great for absorbing bacteria, but does not absorb the water. A gastrointestinal health supplement called BioSponge® came on the market in the early 2000s through the company Platinum Performance. The product is a purified clay powder that binds the toxins, and also binds the water, so that the horse loses fewer fluids in their equine diarrhea.

While absorbing the bad bacteria and toxins is important, also providing good bacteria in the form of probiotics can be very helpful.

“Probiotics are very variable in their efficacy, but there are some bacteria that are known to be associated with gut health,” Dr. Heidmann noted. “The good bacteria in people, and in horses, that has the most data for being helpful is Saccharomyces Boulardii. Old-fashioned brewers yeast is also Saccharomyces, but it is a different species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

“One of the best ways to re-establish healthy flora is Transfaunation, which is taking a healthy horses manure, filtering it, and then tubing it into the sick horse,” Dr. Heidmann added. “That is one of the most dramatic treatments out there. It provides the good ‘bugs’ that the horse is losing through the diarrhea. You will often see foals eating their mother’s manure. It is an instinctual habit to get the good bugs into their stomach. We only do that in the sickest of cases. Whatever the route, it makes a big difference to provide the good bugs because that creates the environment for the gut to heal.”

While some antibiotics are warranted in the right situation, Dr. Heidmann pointed out that they are not necessary as often as people would think.

“With people or dogs, if we get Salmonella or some other intestinal infection, we almost always go on antibiotics, but because antibiotics are the cause of many cases of colitis in horses, in general, that is not the best strategy,” Dr. Heidmann stated. “There are a couple of exceptions. Clostridium difficile does respond to antibiotics, metronidazole being the most common one. For Potomac Horse Fever, Tetracycline broad-spectrum antibiotics are the best.”

Biosecurity measures should also be taken to protect healthy horses from an infectious barn-mate. Dr. Heidmann recommends complete isolation of the sick horse while it is ill, and for a minimum of two full weeks after the infection has been clinically resolved. This includes no horse-to-horse contact, as well as no shared use of wheelbarrows, pitchforks, etc.

Molecular and DNA testing can be done to make sure that the horse is infection-free, however, Dr. Heidmann warns that testing can be problematic.

“There is a very high number of false negatives, meaning there is truly some infection there, but the lab cannot find it,” Dr. Heidmann stated. “There can be times when the horse is shedding bugs, but the tests do not pick it up. The state-of-the-art standard of care is a DNA test called ‘PCR’, and yet you still have to do multiple tests to get a positive test and get a diagnosis. Still, the best way to be safe is to continue testing until you are sure.”

Complications of Equine Diarrhea

Dr. Heidmann warned of common complications in severe diarrhea cases, laminitis being highest on the list. With the sickest of horses, it is unfortunately not uncommon for the veterinarian to get the gut fixed over three to five days, and then find that the feet have started to become very inflamed due to toxins in the bloodstream. If the horse loses the lining of its intestine, then the good and bad bacteria that are supposed to be contained in the intestine can “leak” out into the bloodstream and are free in the abdomen. Those bacteria are then dying either from an attack by the immune system or antibiotics, and they release endotoxins into the bloodstream, which along with other inflammatory products, can cause laminitis.

Another serious complication is blood clotting. The sick horse may become very low on blood protein when the bowel lining is damaged, which can cause clotting abnormalities. The horse may have difficulty clotting or they may become prone to abnormal increases in clotting. The horse might seem better, and then it will develop a clot somewhere in the body. It can be anywhere, but it is most often in the intestine itself, which is usually fatal. In general, horses like this are treated with supplemental protein in the form of plasma. In some cases, the veterinarian will also provide anticoagulant medications.

Although some cases of equine diarrhea are brief and easily resolved, Dr. Heidmann reminds that serious cases can go downhill fast, and it is important to refer to an expert.

“The biggest sign of a problem is duration,” Dr. Heidmann concluded. “If it is one day, it could be that they had a bite of bad food or something simple. If there are fevers or lethargy, those are instant warning signs. If it lasts for days, or if they go off their feed, those are instant warning signs. That is when you should call your veterinarian right away, especially because as they start to go downhill, these complications really amplify. The worst cases are the ones that have been smoldering for a day or two.”

Dr. Heidmann and the veterinarians at Palm Beach Equine Clinic are always available and encourage owners to contact the clinic at the first sign of a problem.

Horses are competing around the world more than ever. It is important for all horse owners to implement a routine for vaccinations and biosecurity protocols to keep their horses healthy. Many infectious diseases are easily transmitted between horses and spread quickly through a stable or showground if the proper measures are not taken. The veterinarians at Palm Beach Equine Clinic are very experienced with isolation cases and always available to discuss the important steps that should be taken to maintain effective biosecurity protocols. Palm Beach Equine Clinic encourages owners to reach out to their veterinarians at any time for more information or alert doctors of a suspected potential risk.

Preventative Equine Healthcare

The best first line of defense for horse owners is to maintain current equine vaccinations. Equine Influenza and Equine Herpes Virus (EHV-1) are two deadly diseases that are highly contagious and should always be included in a routine vaccination program. In the United States, it is now required for all horses attending a USEF competition to be vaccinated for Equine Influenza and EHV-1 prior to any event. Official documentation of vaccinations being administered within the previous six months must accompany the horse to the competition.

Vaccination does not guarantee absolute protection against any diseases, and biosecurity measures should also be taken as added protection.

Biosecurity is a preventative measure taken to reduce the risk of transmission of infectious diseases by people, animals, equipment, or vehicles. Biosecurity is important at all times, even when an outbreak has not occurred.

The Stress of Travel

Owners that use commercial transport for their horses should confirm that the trailers have been disinfected between each shipment. Trailers should always be well ventilated, and horses should be provided with fresh, clean water at all times. The stress of travel can decrease a horse’s immune system, causing more vulnerability to disease. It is important to monitor your horse’s behavior and health closely before, during, and after traveling.

Preventing the Spread of Diseases

Simple day-to-day practices in health care and hygiene are also very important in reducing the risk of contracting an infectious disease. Washing hands between grooming horses and regularly cleaning grooming supplies can reduce the spread of infection. When attending a horse show or moving horses to a new location, a footbath for all persons entering or leaving the barn at each doorway can be effective in disinfecting shoes to reduce tracking disease into the barn. If horses are showing a depressed attitude, have stopped eating, are running a fever, and/or have a runny nose, contact your veterinarian immediately. Early medical attention for an infectious disease makes a large impact on the recovery of your horse and the equine community’s safety.

The best way to safeguard any horse’s health is to keep the immune system strong with support from a suitable nutrition and exercise program. Vaccinations, a proper deworming program, and biosecurity practices will provide additional protection.

As one of the top equine medical centers, Palm Beach Equine Clinic has the pleasure of working with many highly specialized, world-class equine professionals. Dr. Peter Heidmann, DVM, DACVIM, is a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, as well as the Owner/Hospital Director of Montana Equine Medical and Surgical Center in Three Forks, MT. In conjunction with a busy schedule of managing Montana’s leading full-service equine referral practice, Dr. Heidmann joined the team at Palm Beach Equine Clinic in Wellington, FL, for the first time this past winter to share his expertise in internal medicine. Dr. Heidmann is scheduled to return again for the 2017 winter season.

Dr. Heidmann grew up in New England and in the year 2000, graduated from Tufts University in Massachusetts with his veterinary degree. He completed his required internship at Arizona Equine, followed by a one-year surgical fellowship at Oregon State University. Beginning in 2002 to 2005, Dr. Heidmann completed a residency for Internal Medicine at the University of California, Davis.

Following his residency in 2005, Dr. Heidmann began his career with a private veterinary practice in Montana. Then an unfortunate turn of events quickly changed his new employment. Dr. Heidmann’s predecessor in Montana passed away in a tragic car crash on the last day of the year, and Dr. Heidmann stepped up to continue to build the practice left to him. Over the last ten years, Dr. Heidmann has developed Montana Equine to include two satellite offices and six senior veterinarians, plus become the leading referral hospital in the state.

As a Board Certified Internal Medicine Specialist, Dr. Heidmann specializes in neonatology, infectious disease, and ultrasound. In addition to his core internal medicine interests, Dr. Heidmann’s strengths also include advanced performance evaluations.

Dr. Heidmann was recruited by Dr. Scott Swerdlin, President of Palm Beach Equine Clinic, during the fall season of 2015. Dr. Heidmann’s wife, Allison, is a professional jumper and enjoys showing at the Winter Equestrian Festival (WEF). When Dr. Swerdlin offered Dr. Heidmann the opportunity to join PBEC and spend the winter in Wellington, he jumped at the opportunity.

“It worked out really well for me, for family reasons as well as professional reasons, to come down and do internal medicine specialty work during the winter in Wellington,” Dr. Heidmann detailed. “It is nice on the professional front, because Montana is the fourth biggest state, but the second lowest in per capita people. There are a lot of horses there, but there is not a lot of specialty horse work during the winter, so it was really nice to be able to work with the caliber of athletes that are at the WEF and come into Palm Beach Equine Clinic.”

“The facilities are really nice, and I am excited about the improvements they are making, because what was already there was incredible,” Dr. Heidmann said, pointing out recent renovations that are currently underway at the clinic. “It is great to have those resources at your fingertips, not just imaging and equipment, but the staff and variety of expertise. In Montana, I have six or seven veterinarians to bounce ideas off of, and all of a sudden at PBEC I had 30 people with different perspectives, and different backgrounds, and training. You get to see different ways of doing things and see how things can be done even more efficiently. I really emphasize the staff as much as the bells, whistles, and equipment.”

“There are not a lot of us Board Certified Internal Medicine veterinarians, because it is perceived as kind of an egghead, academic sub-discipline of equine work,” Dr. Heidmann admitted. “But what we focus on, especially in healthy horses like the athletes at WEF, are performance issues. Two of the most common, classic, performance-limiting issues in athletes, and especially in sport horses, are respiratory problems and muscle problems, which can range from quite subtle to severe.

“Muscles problems can be subtle issues that involve mild tweaking in diet or micronutrients, or they can be more severe issues like a horse that ties up,” Dr. Heidmann detailed, describing myopathy. “Similarly with respiratory problems, it can be a mild issue where the trainer or rider thinks that the horse used to be better or just is not performing up to its potential. It can be subtle respiratory problems like shortness of breath, or loud breathing, or slow recovery after work, or it can be more severe things like respiratory infections.”

Muscle issues and respiratory problems are the two main areas of internal medicine expertise, but the specialty can include many other things, such as liver problems, neurologic problems (brain and spinal cord both), and the care of sick neonates (foals).

“With seasonal breeders, that three-month period in Wellington is a high time for foals being born, and there is really a great deal that we can do with sick babies to end up with a healthy athlete in the end,” Dr. Heidmann noted. “Many people do not even realize what is possible with sick babies. It is possible to recover a top-notch performance horse out of a foal that looks quite dire.”

While Dr. Heidmann specializes in internal medicine, he and all of the veterinarians at Palm Beach Equine Clinic are very knowledgeable and experienced in general medicine practices.

“All of us in equine work are put in positions where we are generalists too, but what I really enjoy about being part of the team at PBEC is being able to focus on my true specialty,” Dr. Heidmann acknowledged. “This is what I spent so much time training to do, and to really be able to go in-depth, not just with the performance horses but non-WEF horses that are in the area as well, is a wonderful experience. We can really offer a level of treatment that is relatively rare in private practices.”

About Palm Beach Equine Clinic

The veterinarians and staff of Palm Equine Clinic are respected throughout the industry for their advanced level of care and steadfast commitment to horses and their owners. With 30 skilled veterinarians on staff, including three board-certified surgeons, internal medicine specialists, and world-renowned board-certified equine radiologists in the country, PBEC is known for leading the industry in new, innovative diagnostics and treatments. Palm Beach Equine Clinic provides experience, knowledge, availability, and the very best care for its clients. Make Palm Beach Equine Clinic a part of your team! To find out more, please visit www.equineclinic.com or call 561-793-1599.

More about Dr. Heidmann

Dr. Heidmann sees referrals and consults on cases from veterinarians throughout Montana and has served as an expert witness in many legal, welfare, and insurance cases. He served as the Internal Medicine Specialist for the 2011 Pan American Games in Guadalajara, Mexico, and participated as one of the founding veterinarians of Montana State University’s Bioregions program to Mongolia in 2014. He is Adjunct Faculty at Washington State University’s School of Veterinary Medicine in Pullman, WA, and Affiliated Faculty at Montana State University, Bozeman.